Full digital issue is below. Purchase print copy on our Blurb page.

From the Editor

I recently got back from hiking a forty-mile section of Vermont’s Long Trail. It was the furthest I’ve ever hiked. At the end of the second day, I discovered blisters the size of grapes on each of my heels. I poked them with our spam-cutting knife, and out came jets of fluid. Very udder-like. Very gross. Don’t pop your blisters. They will heal slower, and you may be ostracized for having weepy feet.

We (my brother, three friends, and me) woke up at four AM on the first day, stumbled out of our motel, and into the trees illuminating the wet-leaf-trail with headlamps. It began to drizzle. We’d known the forecast but refused to cancel through sheer pride. Everyone pulled up their rainhoods and arched their backs willing the wetness to subside. I opened an umbrella. The others tried to tease me but quickly became jealous. Hikers don’t bring umbrellas because that would be absurd. I remained dry and aloof the entire weekend.

Hiking dissolves my anxiety. Maybe it’s the exhaustion from constant exercise, the lack of apps and texts, the simple goals (walk, eat, sleep, walk again), or the shared sense of wanting to be at the campsite already, so why don’t we chat about something idiotic to pass the time, hey isn’t wet moss better than toilet paper? Shouldn’t Massachusetts invade Rhode Island and turn it into a county? I sure hope we don’t get stuck sleeping next to a bunch of 30-something Brooklynite hikers, all cheerful and millennial. Something about the trudge filled me with bliss. I felt peaceful.

While I was walking in the woods, I was neglecting my editor duties. This was supposed to be the first issue that came out on time, right at the beginning of October like all good semi-annual literary journals do. Whoops. My best excuse is the record-breaking number of submissions I received, more importantly, the record-breaking number of submissions I loved. This is the biggest issue by far, and there were still some stories I wish I hadn’t cut.

As always, thank you to the authors who built this issue, and thank you to the readers who read it!

J.B. Marlow

Contributors

Fiction

Artisan baker by trade, Alfredo Salvatore Arcilesi (“Rag Doll Symposium”) has been published in numerous literary journals. Winner of the Scribes Valley Short Story Writing Contest, he was a Pushcart Prize nominee, and twice nominated for Sundress Publications' Best of the Net. In addition to several short pieces, he is currently working on his debut novel.

Vance Voyles (“Cut Through Everything”) spent the last twenty years as a police officer, seven of which were spent investigating Sex Crimes and Homicide in Central Florida, sitting in long conversations with rapists and murderers making up stories to help them confess their crimes.

His fiction, nonfiction, and poetry has been featured in Burrow Press Review, Flash Fiction Online, The Short Story Podcast, Ghost Parachute, Bull, Creative Nonfiction, Pithead Chapel, J Journal, O-Dark-Thirty, Hippocampus, So Say We All, and Rattle Magazine respectively.

He recently published his first novel, Soldier's Heart: An Evin Walker Thriller, which is available now on Amazon. To read more of his work, feel free to check out his website at www.vancevoyles.com

Shauna Shiff (“Near Flood”) is an English teacher in Virginia, a mother, wife and textiles artist. Her poems and short stories can be found in Stoneboat Literary Journal, Atticus Review, Cold Mountain Review, Green Ink Poetry, Cola and upcoming in others. In 2022, she was nominated for Best of the Net.

Jack Croughwell (“The Rascals”) is an emerging writer from Lowell, Massachusetts. His work has appeared in Teleport Magazine, Stone Quarterly, and The Offering. He carries a yellow pen.

Kate Bergquist’s (“The Distant Light of Interstellar Objects”) short fiction appears in Idle Ink, The Chamber Magazine, Rural Fiction Magazine and elsewhere, and includes a nomination for Best New American Voices. She holds an MA in Writing and Literature from Rivier College. Her inspiration is drawn from the landscape and the people of New England, especially New Hampshire and along the Maine coast, where she lives with her husband, several old rescue dogs and a petulant ghost. Kate can be reached at: firstlightkate@gmail.com.

Christine Vartoughian (“The Only Way Out Is Through the Window”) is an award-winning Armenian-American writer and director whose work has shown at Lincoln Center, Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI), and whose feature film about love and suicide, Living with the Dead: A Love Story, has been awarded the Audience Choice Award at Art of Brooklyn Film Festival, Best Feature Film at Aberdeen Film Festival, and is available on Apple TV and Amazon, in the U.S. and internationally. She is the co-founder of (Screen)Play Press, a publishing company for yet-to-be-produced film scripts. @christinewritesaboutyou www.christinevartoughian.com

Joshua Sabatini (“Jack and the Trumpet”) was born in Hartford, Connecticut. In October 2002, he moved to San Francisco, California. He's currently on retreat in Katama, Massachusetts. His 2023 published writings include "Pagodians" in Still Point Arts Quarterly, “In the Pine” and “In and Out” in The Closed Eye Open, “The Crocus” in Daffodil Cosmic Journal, “Ivy Anne” and "Susitna" in Die Leere Mitte and "The Winged" in In Parentheses. The author can be contacted at JoshuaSabatini@gmail.com.

Terence Patrick Hughes (“So You Want To Be a Rock and Roll Star”) writes fiction, poetry, and drama. Recent short stories were published with the Stonecoast Review, Ignatian Literary, and Portrait of New England. His theatre work has been developed and produced around the USA and internationally, and published in university literary magazines, as well as Best Contemporary One-Act Plays. The New York Times noted that his work “…explores heavy subject matter with humorous dialogue and strong characters”. Born in Lawrence, MA, Hughes lives with his wife and two children in Woodstock, NY.

Nonfiction

Billie Pritchett (“Past Life”) is an assistant English professor at Kyungnam University in Changwon, Korea. He has an MFA in Creative Writing and an MA in TESOL from Murray State University.

Lael Cassidy (“Portrait”) writes poems, stories, and essays, and her work has appeared in Headline Poetry and Press, Silver Birch, Underwood Press, and Beyond Words. She has also written sixteen nonfiction children's books. She lives in Seattle, teaches writing, and is currently at work on a memoir. You can find her at www.laelcassidy.com.

Harvey Silverman (“Burnt Offerings”) is a retired old coot who writes nonfiction primarily for his own enjoyment. He lives in New Hampshire.

Visual

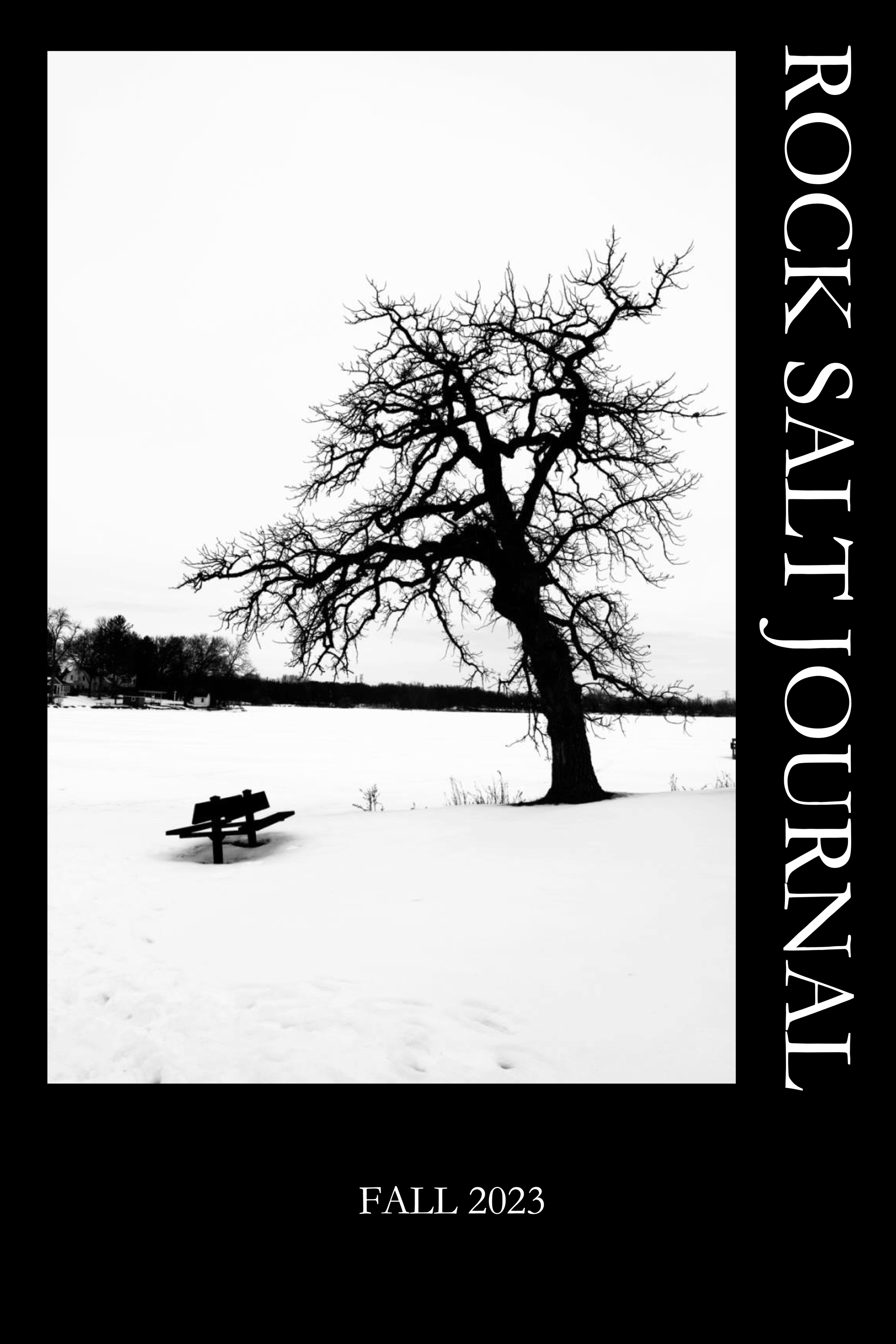

Erik Suchy (Cover: “Portrait of March”, “A Quiet Place”, and “Strangers”) is an amateur photographer and aspiring writer from St. Paul, Minnesota, having completed a B.A. in Creative Writing from Metropolitan State University. His visual work often incorporates themes of isolation and disharmony from both natural and digitally altered perspectives, although he frequently pursues a variety of different, cross-genre ideas alike.

GJ Gillespie (“Raft of Medusa #3”) is a collage artist living in a 1928 Tudor Revival farmhouse overlooking Oak Harbor on Whidbey Island (north of Seattle). In addition to natural beauty, he is inspired by art history -- especially mid century abstract expressionism. Winner of 20 awards, his art has appeared in 60 shows and numerous publications.

Willy Conley (“Boat House I, Westerly, Rhode Island” and “Little Red Schoolhouse, Chester, Connecticut”), a former biomedical photographer, has photos featured in the books Photographic Memories, Plays of Our Own, The World of White Water, Listening Through the Bone, The Deaf Heart, No Walls of Stone, and Deaf World. Other publications: American Photographer, Arkansas Review, Baltimore Sun, Carolina Quarterly, Big Muddy, Folio, and 34th Parallel. Conley, born profoundly deaf, is a retired professor and former chair of theatre arts at Gallaudet University (the world’s only liberal arts university for deaf and hard-of-hearing students) in Washington, D.C. For more info about his work, visit: www.willyconley.com.

Donald Patten (“Rebecca” and “Nancy Lee”) is an artist from Belfast, Maine and is currently a senior in the Bachelor of Art program at the University of Maine at Augusta. As an artist, he produces oil paintings and graphic novels. Artworks of his have been exhibited in galleries across the Mid-Coast region of Maine. His online portfolio is donaldpatten.newgrounds.com/art.

Marjorie Williams (“On the Cocheco”) is a photographer from Reno, Nevada. Their work deals with the transformative powers of nighttime, the beauty of human relationships and the magic of the mundane. They work with both analog and digital photographic processes to capture not only the look, but the feel of the world they see. They have their Bachelor’s in Photography with a minor in Museum Studies from the University of Nevada, Reno. They spent a year and a half living and working in Portland, Oregon, spent Summer 2022 traveling across the country photographing, and they are currently living in New Hampshire.

Jennifer Shneiderman (“Watchful Conductor”) is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker, writer and visual artist. Her work has appeared in many publications, including: Yale University’s The Perch, UCLA’s Windward, The Rubbertop Review and Harpy Hybrid Review. Her work has been featured on the Read650 podcast and she received an Honorable Mention in the Laura Riding Jackson 2020 Poetry Competition.

Rag Doll Symposium Fiction

Alfredo Salvatore Arcilesi

A sensation.

Somewhere in the darkness. Soft.

Warm.

Spreading.

Familiar.

Sweetly familiar.

I don't wanna wake up, Andie thought to herself. To her.

Ultrasound-resolution snapshots of her—the owner of the sweetly familiar: An awning of wispy bangs poorly concealing the remnants of acne.

Endearing moles forever at risk of falling into severe dimples. Crooked smile full of crooked teeth.

Eyes a squirrel's winter-long regret about the prized acorns that got away.

And the sweetly familiar itself: lightly freckled, naturally fragrant flesh stretching over perfectly moulded cartilage to produce the finely pointed nose unique to Heather.

The sensation—a feathery tickle against Andie's own bumpy nose—beckoned her to wake up.

Let me sleep.

But the tickling intensified. Heather’s persistent nose rubbed against Andie's, achieving searing friction.

This better be good.

Bracing for light—even if only the dim shaded bulb on the nightstand—Andie opened her eyes and was rewarded with the darkness of Heather's close countenance.

I'm awake, I'm awake.

But Heather seemed neither to notice nor care.

Andie swivelled her head in a spasmodic arc, trying to untether herself from Heather's abrasive nose, but a keen Heather mirrored every evasive direction. She tried pushing the nuisance away, but the nuisance had prepared for this counterattack, pinning her arms.

What're you doing?

Heather continued the assault at her leisure.

Prophesying the personal pain of such a tactic, Andie shot her head forward, but the headbutt failed to make contact with the anticipating Heather. Once more, she projected her forehead; once more, Heather mirrored the motion in reverse.

The agonizing tickling and impenetrable darkness persisted.

What the fuck’re you doing?

Andie blinked vigorously, unable to grip the opaque nothingness of Heather's face. A spike of anxiety pierced but did not defeat the overwhelming tickling.

It's happened!

Sharper spikes of anxiety, whetted by an ambient lifelong fear.

I'm mute and blind!

Exaggerated blinking tested her new disability.

Tears failed to wash away the darkness. Failed to soothe the tickling ravaging her nose.

Can't you see I'm fucking blind, Heather?

A gust of wind banished the darkness, but not the awful tickling, allowing terrible light to stab Andie's unprepared eyes. Behind sealed lids, she waited for the jolting pain to subside, relishing the jagged throbbing, for it promised a chance of sight. A chance of seeing Heather.

Like a newborn's natural foray into optics, Andie studied the world between adjusting

blinks:

Hands stretched out on either side of her, free of Heather's shackles.

Blink.

The left a tight fist.

Blink.

The right upturned, open, reaching for something. Blink.

Or someone.

Heather?

Andie stared at the motionless hands shrouded in night's gloom, willing them to form the motions that would “speak” Heather's name.

They remained still.

She attempted “speech” again and again, each time forging a spike of anxiety with a message not of blindness this time, but of something else.

Sleep paralysis. Recalling the frequent occurrence blunted the spikes.

Sleeping on my stomach again.

But I'm not allowed to sleep on my stomach anymore. Why?

I don't know.

Another breath of cold air inspired movement. Vexed that Heather would leave the oscillator on at what felt like maximum power during a bitter winter night, Andie tracked the stirring to her right. Things poked out from the wrist of the unfulfilled right hand. Tiny.

Gossamer. White. Dancing in the breeze, seemingly matching the tickling on her nose without contact.

I know what you are.

Andie crossed her eyes, directed blurred sight upon the tip of her nose, and barely made out the tail-end of one of the tiny white things clinging there.

You're not Heather’s nose!

Fire raged beneath her face, stoked by the fraud that was the tiny white thing she struggled to identify. She tried to wipe the obstruction away, but sleep paralysis forced her to try another way. Attempts to move her head reported the same incapacity. Her tongue fared too short to reach the anomaly, while funnelling breath upward only contributed to the tiny white thing's dance. And its fraudulent tickling.

You'll never be Heather’s nose!

Andie glared at the other tiny white things spilling from her wrist.

None of you will ever be Heather’s nose!

One of the flimsy objects quivered in the swift breeze.

You rhyme with her...

Faster quivering.

But you're just...

Loosening itself from her wrist.

You're just a... a stupid feather!

The tiny white thing—indeed a feather—flung itself toward her. The oncoming feather grazed her nose, instigating a fresh tingling sensation, then flitted away, leaving the original feather stuck to her nose to continue the annoying assault.

Andie eyed the feathers' cousins, pouring from her wrist, threatening additional attacks.

I gotta get Heather to sew that up.

The fire beneath Andie's face simmered to a temperature of reminiscence. A heat calibrated to emulate Heather's delicate embrace. For a moment, she quieted the tickling on her nose, and she and Heather became Celsius and Fahrenheit, their trivial differences set aside to form a mutual climate. A love affair between disagreeing degrees, matched only by the winter jacket Heather had gifted her.

Why am I wearing a jacket in bed?

Andie's desperate eyes searched the farthest reaches of their sockets. She stared at her open right hand, then adjusted her vision to include her closed left fist in the narrow frame of vision. The immovable things were her means of communication with a world that barely listened to the speaking. These bony, fragile tools possessed the history of Andie and Heather in their joints, their lines, their movements; possessed their arguments, their flirtations, their declarations of love, their wordless explorations of flawed bodies. They articulated every syllable, every inflection, every nuance their shared body language spoke.

But Heather was nowhere to read Andie now.

Dread filled Andie, then a painful swig of frigid air. Countless icy teeth and claws gnashed and slashed at her hot innards, melting to a refined tickle in her dry throat—as if Heather rubbed her there with her sweetly familiar nose. Increasing pressure and vibration created an alien discomfort, and when she achieved that sense of unpleasant fullness, she braced herself, wishing for dreaded deafness as she expelled a pitiful timbre of inarticulate wind.

Andie winced at the pathetic sound of her wretched voice, immediately cutting off the gauzy second syllable of Heather's name before it could further pollute the silence.

The unpleasant fullness dissipated. The pressure released.

The vibration returned to stillness.

The tickling buried itself in her unpracticed vocal cords. Tears, not Heather, heeded her call.

Where the fuck are you, Heather?

A scream tore through the silence, a noise Andie could never aspire to create.

Heather?

The scream rose in volume, in agony.

She's having another nightmare.

Andie struggled to push her head to the right, but sleep paralysis had other plans. Still, memory showed her what she had seen many a night: a “sleeping” Heather, bathed in perspiration, a corner of the pillow cover or end of the blanket crammed into her gagging mouth, the poor thing trapped in the recurring nightmare, where she was reduced to a vulnerable child, forever choking on the sock her ashamed mother forced her to keep in her mouth for countless hours, her mother's incessant credo—“A girl who can't speak has no use for a mouth”—singing against Heather's screaming.

It's okay, doll, Andie helplessly cooed. I'm here.

Andie glared at her stricken arms to awaken from the damned sleep paralysis.

I'm awake! she yelled at her left arm. To the right: I'm fucking awake!

As the excruciating concert wore on, Andie fixed her eyes on the open seam of her jacket sleeve, its gaping mouth seemingly producing the agonizing screams. One of the feathers flitted toward the screaming as if sucked by the noise. Another followed, seemingly beckoning her to follow its trajectory. Even the fraudulent feather tacked to her nose had had enough of imitating Heather's rubbing nose and flew in the direction of the screaming—flew not adjacent to her, where Heather suffered through her nightmare, but ahead of her, where the bed's headboard and the wall beyond were just out of sight.

Screaming can't come from there.

An epiphany both relieving and perplexing: Heather can't scream.

Indeed, the perpetual soundtrack of distress was much too distinct, soaked in the clarity of the regularly-speaking.

Andie forced her head up and forward for a better view of the source of discordance, barely managing to rest her chin upon a hard, cold surface.

Where's our bed? My pillow?

She tried to extend her range of motion, but the cursed sleep paralysis established its

barrier.

The screaming dropped into an octave of frustration for a quick bar, guttural notes Andie begrudgingly adopted as the anthem to her own frustration.

The strained vocals abandoned this reprieve, resuming its song of pain. So, too, did Andie's eyes rise with the notes, straining to see something—anything!—just under their top lids. Twin images of blurry eyelashes filled her field of vision, through which she could see a dark, sleek surface that ended in a massive spiderweb.

No wonder Heather's screaming.

She's not, she reminded herself. She can't! But the spiders!

Andie's limited sight followed the strands of web, their simultaneous diverging and converging paths crooked, muddled with helter-skelter clots, knots, and lazy asymmetrical patterns. The work was devoid of famed arachnid artistry.

I gotta find and kill the spider for her.

Her eyes hunted, seeing eight legs where none existed.

Where the fuck are my legs?

Her brain sent messages to them but received reminders of sleep paralysis.

Exasperated, Andie concentrated on locating the spider. Sight settled upon a glob of web material sitting to one side, pressing against the web from behind without snapping the strands. Glistening red stained the off-white mass.

Do spiders bleed like we do?

She couldn't recall any colours from her previous Heather rescue missions. Blood and guts had always been carefully collected and concealed by exaggerated clumps of tissue or smooth-soled dollar store slippers, thrown away with neither smear nor stray piece.

If only they were made of tiny white feathers, then Heather might kill them herself. But then I couldn't rescue her.

A scream from somewhere beyond the ugly web and uglier clump of red-splotched ball of material.

Do spiders scream?

She didn't know. Didn't want to know, what with the numerous murders by her hand.

Another scream. Human, garnished with animality. An abrupt choke reduced the screaming to an intermittent rhythm of panting and crying.

The hunk of web throbbed in sync with the breathy melody. A painful bark announced the arrival of twin spiders crawling over the bulbous horizon. Large, spindly things. In Andie's mind, doubtless plump with tiny white feathers.

The binary arachnids halted in unison, staring at Andie with a multitude of hidden eyes that asked the same question: “How are you going to protect Heather?”

The panting/crying intensified, neglecting its metronome.

The spiders clenched the glob of web, impressing their spindly legs into the mass, giving Andie the impression of something hollow and soft. Intoxicated with heavy deja vu, she felt the spiders and their imprint as a single hand upon her stomach. Felt the tiny protest against the disembodied palm. Felt the barely perceptible rise and fall underneath the palm.

Andie diverted her eyes from the spiders, but she still felt the ethereal palm against her stomach, the rise and fall of burgeoning life within, communicating its own rendition of her and Heather's soundless language.

Rise and fall.

Rise and fall.

Rise Andie had, mere hours ago, sliding out from under Heather's anchoring hand.

Andie felt the life within still communicating, unaware contact had been broken during the quick escape from a cozy bed, oblivious to Andie's hasty change from toasted pajamas to untoasted winter wear. She turned to an inquisitive Heather, answering those acorn eyes with a flourish of hands, communicating her need for fresh air. And before Heather's hands could espouse cliched warnings of the perils of the late hour, the harsh weather, and remind Andie she had two people to think about—made all the more ominous by her official use of “Andrea”—Andie left.

Traffic was sparse, the last of the illuminated businesses camouflaged with the night. No matter the pace or direction travelled, Andie still felt Heather's strangling umbilical cord reeling her back to their womb-like apartment. Still felt Heather's hand upon her bulbous stomach, transmitting love, admiration, and awe to the life within. Underneath the positive trifecta, however, there lived the lingering inverted trinity of anger, resentment, and jealousy, for genetics, in all of its indiscriminate wisdom, had long ago deemed Heather unfit for childbearing.

Aimless though she believed her steps to be, Andie instinctively slowed as she approached the building. The filmy streetlamp was far too bright, too akin to Heather's omniscient eyes, coaxing Andie to review her surroundings. Despite its discreet and welcoming design, the bland building exuded an aura of stigma and harsh judgment. Andie ignored the condemnation by counting the slightly uneven steps to the front door, knowing there were three—always three. Three easy steps. And a ramp. Easy access to a life in need of correction. A new life.

Andie knew she could indeed achieve a new life beyond those sliding doors, but knew that, upon exit, it would be a certified life without dear Heather.

As if sensing the building's controversial business, the baby kicked, and like a trained horse responding to a spurred heel, Andie moved on, wondering if she would ever muster the moxie to pass through those sliding doors during hours of operation.

Hands buried in the warmth of the jacket's pockets—and far too close to the sentient creature beneath the fabric—Andie found herself not only toying with thoughts but something else. She withdrew her right hand, and between her fingers saw a bent tiny white feather, flailing in the cold wind. Pivoting her arm, she saw the seam—wider than the last time she had laid eyes upon it during a similar walk for “fresh air”—in the cuff of the jacket, the deflated sleeve having lost most of its voluptuous originality.

Andie imagined a similar opening along her abdomen. Imagined reaching in and removing her tiny white feather.

If only it was that simple.

A flash of the building in her wake, and the inspiration, along with the feather, flitted away in the bitter wind.

As cold breaths of air slowly defeated Andie's jacket, her worn boots detected uneven gravel well past the transition from smooth sidewalk. Down a quiet road she had never traversed, she found herself within the throes of longer, deeper chasms of darkness, sporadic, weepy-eyed streetlamps teasing tangled brush and sinuous, nude trees.

She, too, felt nude, but somehow freer.

The mysterious darkness beyond the last visible streetlamp illuminated a thought: I can keep going.

Her stomach ached with the kicks of countless babies, forcing her to stop. Alarmed by the swiftness of the onslaught, she felt something she hadn't since first daring to hold Heather's hand for all the world to see. Not the kicks of countless babies, but the fluttering wings of excited butterflies.

I can keep going!

In the invigorating darkness between tired streetlamps, Andie's mouth ached, both from the numbing cold and the lengthy lack of practice those deprived muscles had in performing a smile. For the first time in months, she no longer felt like an incubator to Heather's hopes and dreams, a lifeless machine providing life to a living, breathing miniature but weighty anchor, but a weightless butterfly sanctuary whose very inhabitants would whisk her off of her exhausted feet, and transport her to a place where mind and body were her own.

Keep going!

Her legs believed the hype, propelling her toward a terrifying yet exhilarating unknown. A pale pair of silvery eyes pierced the dark vanishing point of the quiet road ahead.

She was faintly aware of the glaring negatives of this compulsion, instead savouring the gluttony of well-deserved selfishness.

The pale eyes grew brighter. Closer.

Butterfly wings pushed her forward. Baby kicks—or the fresh memory of them—threatened to pull her back to Heather, and the seemingly already-lived life she had fervently planned for the young trio.

The eyes moved fast and erratically along the road, illuminating Andie's route to freedom.

Her right hand detected another loose feather.

I gotta get Heather to sew that.

Her enthusiastic legs tripped on the old, automatic thinking. She regained footing, helped by Heather's firm grip on her stomach. Heather's property.

The eyes blurred into a single spotlight, blinding, roaring, racing toward her. The baby issued a tremendous kick.

Darkness replaced the spotlight, somehow equally blinding.

Andie danced with minutes and millennia in timelessness until oblivious numbness spawned a sensation.

Somewhere in the darkness.

Soft.

Warm.

Spreading.

Familiar.

Sweetly familiar.

I don't wanna wake up.

But the crying insisted.

Not the blaring adult female screaming that had paradoxically lulled Andie to the peaceful darkness where recent memory dwelled, but a quieter, tinier, reassuring song whose hypnotic quality gently lifted Andie out of her black limbo.

Between blinks, she rediscovered her predicament: outstretched arms bracketing her peripheral, the left hand curled in a tight fist, the right hand open, awaiting acceptance, her permanently paralyzed means of communication rendering her forever mute; the tiny white feathers continuing their way through the jacket cuff's enlarged seam, some clinging to the opening, seemingly hesitant to experience their newfound freedom, while others took flight without second thought; the shattered windshield where she began to see and understand the car manufacturer's safety design rather than the intricate abstract web-work of an elusive yet brilliant spider; alas, there were the twin spiders and their glob of reddened web—dead feminine hands clenching a deployed, blood-stained airbag.

For all the human and vehicular carnage, Andie felt no pain. Felt nothing but the tickling sensation inspired by severed and confused nerve endings unable to see and comprehend the car before her and the tree behind her.

From somewhere behind the busted windshield, the crying of a newborn baby lamented its terrible start in life.

I'm sorry your mommy is dead, Andie hopelessly transmitted. The baby cried louder: “I'm sorry your baby is dead.”

Andie focused her numb senses on her stomach, the crushed filling of a gruesome sandwich. She mentally kicked the baby, receiving the stillness for which she yearned.

I can sleep on my stomach again.

The bent hood of the car was cool under her cheek.

Like its deceased mother's labour cacophony, the baby's crying wooed Andie into a masquerade of slumber. The nothingness was seductively delicious; the more obese she became indulging in a diet of pure nirvana, the lighter she felt. From infinite seams on her deflating being, tiny white feathers went wherever such things go.

There was a final sensation. Somewhere in the darkness.

Sweetly familiar.

Raft of Medusa #3 by GJ Gillespie

Cut Through Everything Fiction

Vance Voyles

She is standing on the side of the highway slicing into an apple when the horn blast from a passing eighteen-wheeler makes her jump. Jerking the knife, the blade cuts into the skin just below her thumb opening a deep gash.

He is leaning against his backpack tightening the laces on his boots and doesn’t notice the knife or apple fall to the ground at her feet, but her sudden sharp intake of breath makes him look up. At the sight of blood dripping from her hand, he stands, pulling the sweat-stained balaclava from his head, and instinctively presses it into her wound.

“Don’t,” she says. “That’s disgusting.” But he waves her away. Her eyes sting, and she grimaces against the pressure.

His hair sticks to the side of his head just above his ears, and he loosens his grip to peek under the cloth before clamping down again, looking into her eyes.

“Tell me a story,” he says.

“No,” she says, annoyed. She tries to pull away from him, but his grip is strong. “Let go. I can handle it.”

“Please,” he says. “Just one story. It’ll take your mind off.”

She squints at the pain. “Which story?” she asks, and he smiles at her, and the memory of the man flashes in her mind; his graying stubble, his dimpled grin. She’d crumpled to the floor when they told her. It happened in an instant, they said. He hadn’t suffered. But all she heard was the roar of crashing waves in the silence that followed. He hadn’t suffered. How could they really be sure? Isn’t that just a thing that people say?

“This one,” he says, raising his free hand. “Tell me this story.”

She blinks hard, returning his smile. “That’s your story,” she says.

“I know, but I like the way you tell it.”

They are standing on the side of the road waiting for a bus to take them back to town, back to civilization, hot showers, and cold beer. Cars and trucks rip past them, and the gusting wind rattles through their salt-stained clothes. She brushes a strand of hair back from her face and looks at him. He smiles at her the way the man always did.

“Fine,” she says, shaking her head. “You were what, eight years old?”

“Seven,” he says, pushing down the thick wool hiking sock to show her the pale thin line of a scar cutting across his shin. “I got this one when I was eight.”

“Are you sure,” she asks. She stares at his sun-burned face, and the dirt from two weeks wandering through the wilderness, following a trail they all took together so many years ago. She didn’t want to come. It was a stupid idea, reckless even. She was too old for this. She told him as much when he landed on her doorstep with two backpacks and his weatherworn map.

“We need this,” he’d said. “Consider it his deathbed tour.”

She’d laughed at that, albeit through the tears, because isn’t that exactly what the man would have called it? She was just glad he hadn’t made t-shirts.

But now, bleeding on the side of the road, with the two weeks at an end, the world is still here, waiting to swallow her back up. She shakes her head. Two weeks isn’t enough.

A rusted old jeep rumbles by, and she flinches.

“Yes,” he says, shaking her from her memory. “I’m sure. I was seven when I got this one,” he says, raising his hand again.

She grabs it with her free hand between his thumb and forefinger, and touches the thick scar, marveling at how hard it is. “Seven? You’re sure?”

“Sure,” he says, pulling his hand back.

“That would have made me —”

“Twenty-seven,” he says.

“Twenty-seven,” she repeats, almost nostalgic now. “I was a baby.”

“I’m twenty-seven,” he says, raising his shoulders a bit.

“I know,” she says. “Still a baby.”

He raises an eyebrow, and she ignores it.

“I didn’t want you to go,” she says. “Back then, you know? He made me.”

“He was like that.”

“He was like that,” she says, nodding, “but you wanted to go alone. An adventure, you’d said. Be the lonesome traveler.”

“Just the start, I guess," he says, gesturing to their surroundings. Clouds run across the sky, settling around the mountains in the distance.

"Well, I was against it.”

“Adamantly, as I recall.”

“And I was right, wasn’t I?”

He doesn’t answer. Instead, he shakes his head and smiles.

“I was,” she says. “And you know it.”

“I clearly survived,” he says.

“Just barely.” She stares out across the horizon. Dusk is creeping up on them, and a line of amber streetlights blinks to life, mixing with the setting sun and running the length of the highway, twinkling out into the distance.

“So, you forbade it,” he continues.

She shakes away her thoughts. “Of course, I did, but he was having none of it. ‘It’ll be fine,’ he said. ‘Let the boy wander,’ he said. ‘You remember that feeling, Sweet? Being miles away?’”

“It was only a mile,” he says.

“But you were six,” she says.

“Seven.”

“I think you’re wrong about that.”

“I’m not,” he says. “And a mile is nothing. Just down the street.”

“It didn’t feel like nothing.”

“No,” he says, finally agreeing with her. “It didn’t. Might as well have been going to Mars.”

“Exactly.”.

“But still,” he says. “It was just a mile. You know how kids think. Nothing could ever happen because nothing’s going to happen.”

“But something did happen.”

He shakes his head. “Of course, it did.”

“Just like I knew it could,” she says, with a satisfied smile.

“Yes. Yes. I know.”

“I said no, but you were dead set, and so was he." She tries to lift the rag from his hand, but he shoos it away. “I was going to follow you,” she says. “Did I ever tell you that? I was in the middle of putting on my shoes, but he came in and gave me that look.”

“Ah yes. The eyebrows.” He arches his own eyebrows up and down comically, and she laughs.

“The infamous eyebrows,” she says. “He was standing in the doorway, leaning against the frame in that way he always did, shaking his head at me, holding my other shoe in his hand, saying, ‘Going somewhere, Sweet?’ And I said, ‘Give me my shoe,’ but he wouldn’t.”

“And he put it on the fridge,” he says, laughing.

“It wasn’t funny.” She huffs slightly. “He knew I couldn’t reach.”

“And you yelled at him.”

“I didn’t yell, but I was stern, the way I had to be with him sometimes. Balled my fists, saying, ‘Give me my shoe,’ but he just laughed.”

“Not mean though, right?”

“No. No. Not mean. His laugh was never mean. He was like a child, he was, so full of...I don’t know what.”

They both stare out at the horizon as lightning streaks across the sky.

“He cut through everything,” he says.

“Yes,” she says. “He did.” After a few seconds, the rumble of thunder crashes. The clouds above them seem to tumble, rolling pink into purple, purple into black. Looking for a fight.

“He loved it out here,” he says, but she shakes her head, not wanting to think about it.

Instead, she continues. “So, I’m standing there, fists clenched, getting redder by the minute, and he reaches down, and he did what he always did whenever I was getting my temper up.”

“What’s that?”

“He kissed me.” She laughs softly. Her cheeks turn pink, and she touches a hand to them, closing her eyes, trying not to smile, or cry. She doesn’t know which. “Like that was an okay thing to do. Like that was just the right time to do it.”

“Was it the right time?”

She nods. “It was.” She opens her eyes and smiles. “He was always right on time, your dad.”

“He was, wasn’t he?”

She nods and lightning crashes again, followed more closely by a rumble of thunder. He looks down at the bloody rag covering her hand, lifts it, and puts it back. “A little bit longer,” he says. “And then we should probably get moving.”

“You get that from him, you know?”

“What?”

“You know,” she says, motioning her good hand at him. “All of it.”

“Not all of it,” he says. “Some of it, maybe, but there’s other parts.”

“Other parts?”

He motions his free hand to her. “Other parts.”

“Maybe,” she says.

He squeezes her hand, and she can feel his heart pumping there, twenty-seven years of blood blazing past arteries, and valves, and slamming into her. It hurts. This cut. This story. Cars continue to rip past them.

“Then what happened?” he asks.

“He took me to bed,” she says. “He was always taking me to bed. Every chance he got.”

“Well, no wonder,” he says. “You are very beautiful.”

She shakes her head. “Not anymore.”

“No,” he says. “Still.”

“Anyway. I don’t know how long it was. Fifteen minutes, an hour. He was like that with time, stretching it out and then cutting it short. Sometimes it felt like I didn’t know where or when I was.” Tears well and settle in the corners of her eyes, but she blinks them away. “But then it ended. With a phone call.”

He looks up at her wearing a sad smile. “But not that time. That time it was me.”

“Yes. You. Crying. Bleeding, apparently.”

“Profusely.”

“Nine stitches worth.”

“It felt like more.”

“It would. Six years old, as you were.”

“Seven.”

“Right. Seven. Anyway, we ran over to get you. I was barefoot, running.”

“Shoe still on the fridge?”

“Exactly. And you were there, with this face.” She reaches out to touch his cheek. “This sad, little face, and he was smiling at you. And you looked at him, and you smiled too, like you had to. Like you had no other choice. You were his brave boy, stopping the bleeding with one of your socks.”

“And he said, ‘What do you have there, big man?'”

“Bloody sock, looks like,” she says, imitating a gravelly drawl. “And you were saying sorry, and that I was right, that you shouldn’t have gone alone, and that you would never do it again, not ever.”

“But he wouldn’t hear it,” he says.

“Nope. He just kept asking how you did it. And you told him about the dog, and the fence, and how your shoe slipped, catching and cutting yourself at the same time. And he was so proud of you, bucking up like you did. Pulling off your sock, wrapping it tight before walking to the lady’s house and asking to use the phone.”

“Said it took a man to do that,” he says.

“Indeed. You were his big man.”

He lifts the bloody rag. “Looks like it’s stopped.”

“Looks like,” she says. “Too bad I didn’t bring a first aid kit.”

“Too bad,” he says, reaching into his pack and producing a plastic bag of triple antibiotic and some bandages. Squeezing some goo onto her cut, he peels the adhesive strips from one, and a behemoth beast of an RV blasts by them, pulling at their clothes, and snatching the thin strips of packaging in its wake.

“Think we’ll beat the rain?” he asks.

“Not if this bus doesn’t come,” she says.

“Soon,” he says. “I’ve got a feeling.” Then he kisses her hand over the Band-Aid and lets go.

She smiles at this, inspecting his work, and another batch of lightning races across the sky. He reaches into his pack and pulls out another apple, handing it to her, and a crack of thunder echoes in the distance. She bends to pick up the knife lying at her feet, wiping it on her pants, before cutting into the apple’s thick, waxy skin. Cars rip by them, and she smiles when the first drops of rain begin to fall.

Past Life Nonfiction

Billie Pritchett

1.

Before my mother, there had been another woman, Britannia, whom my father had loved and married when they were both in their twenties. After a brief courthouse ceremony with three friends as witnesses (“I don’t keep in contact with them,” my father told me. “Shows what friends they were”), my father and his new bride moved into a mobile home, in a trailer park called Fox Meadows. Right away, my father and Britannia began planning their future. Seated on the floor at their coffee table (their dining table), they laid out their goals in a gnarled Mead notebook: one, my father would get a job within the year; two, they would have a baby; three, while he worked (once he found work), Britannia would take on the responsibility of household chores and child-rearing. The plan amounted to only a few sentences on wide rule, but in short order, all was underway. Within the year, my father started work at Ryan Milk, my half-brother Jared was born, and Britannia, well into her roles as wife and homemaker, assumed the role of mother. She fed everyone, cleaned house, changed diapers, and dealt with both her son’s and her husband’s unruly timetables, since in addition to baby Jared’s tantrums—worst were his colicky nighttime spells, when he couldn’t sleep, which was often—Britannia also had my father’s erratic hours to contend with. My father worked the second shift on the assembly line, three to eleven PM, but that was the least of the problem, because he had mandatory overtime, which meant he had to work an extra four hours, sometimes tacked on before his normal shift, sometimes after. Sometimes he wouldn’t get home until three in the morning, and sometimes he had to work an extra day on weekends. To make matters worse, he didn’t receive notice of the next week’s hours until the current week’s end. The ever-changing schedule contributed to the chaos of family life. Britannia wanted help, needed it in fact. She needed my father to bear some of the child-rearing burdens. “All I’m asking,” she said, “is for you to sit with Jared some mornings, give him his bottle, rub his back, change him if he needs changing.”

“Sounds like you’re trying to change me,” my father said.

“Bruce, I mean it.”

“That’s the problem.” He interpreted Britannia’s plea for help as a breach of contract. “We agreed,” he said. “I work, you do this. Division of labor.”

One night, he got home from work and called out hello from the front door. Britannia stood at the kitchen sink, her back to him. “Where’s Jared?”

“In his pen,” she said.

He went to the bedroom and checked, and spotted Jared, asleep in the playpen at the side of their bed, one hand curled into a partial fist. He bent and stopped. If he kissed his son, he would wake him. From the kitchen, he heard the harsh clank of porcelain. Returning to the living room, he saw Britannia knocking around the dishes. He grunted. She didn’t turn to face him. “Are we playing games?” he said. She shook her head. “I know it’s not nothing, otherwise you wouldn’t make the racket.”

“You’d be mad if I spoke.”

“Aren’t I standing here, wanting to talk?”

Britannia removed the pink rubber dish gloves, popping them off at the middle finger. They fell into the sink with a faint slap. She turned around. “This isn’t fun.”

“What isn’t?”

“This,” she said. “Life.”

“Has life ever been fun?” he scoffed.

“Don’t pretend you don’t remember. In high school people thought you were a wild man, into hotrods. They thought you were so crazy you’d do anything.”

“I’d like to know what we’re talking about.”

“Why are you raising your voice? I don’t want to argue.”

“Are you saying I’m not fun anymore?”

“Just I want some of the old life.”

“Here’s what I know. I’m standing in the living room of a house not big enough for a bachelor, let alone a family, my shirt sticking to my back because I work at a milk plant with no windows, no ventilation, my body pouring sweat, all day, all night—” While speaking, he was unbuttoning his shirt in histrionic show, but the uncooperative buttons impeded his effort to punctuate his words with action. By the time he’d pulled the shirt off, its fall felt anticlimactic. “I can’t believe it,” he said. “I have to come home to this?” She moved to hug him, but he stepped back against the coffee table. “Not now,” he said. Had he gone for a walk, he might have realized his stubbornness.

“I love you,” she said, as he pressed the coffee table’s edge further into his calves. She lunged at him with the next hug. His body bent like an air dancer, one of those tube-shaped men on the side of the road, flapping in the wind to attract customers with their breezy antics. She gave up. She sat down on the sofa, head in hands, a mask of bent fingers.

If he remained where he was, legs pressed against the coffee table, feigning stoicism behind a muted face, what kind of person would he be? He clicked his tongue. She didn’t notice his sitting down beside her, but in his trying to wrap an arm around her, she flinched and sidled away.

“You don’t get it,” she said to the wall. “I just want time to relax. A few free hours some mornings would be a major weight off my shoulders.” She continued talking. He only half-listened.

Then he told her what free time he had had to be used productively. He wouldn’t even call it free time. His so-called free mornings away from the plant weren’t all sitting around shooting the bull at the donut shop. No sir. He was trying to get a car-dealing business off the ground with Uncle James. Didn’t she understand? A second job would be extra income. “We don’t want to live in a trailer forever, do we?” He appealed to Britannia’s empathy. He said when he occupied his table at Sammon’s bakery in the morning, talking with his friends and his uncle, their talk was, admittedly, not all about planning for the car-dealing business, not one hundred percent. That said, he was blowing off some much-needed steam. Every shift, his supervisor rode him, egging him to pick up the line, threatening him with pink slips, and so on and so forth. Every night, he went to bed feeling stressed about his job, stressed he would lose it. And to think, they had a child to feed. This worry did a number on his sleep. Or hadn’t she noticed? So he needed his mornings to sleep in a little or else to see his friends, but most importantly to relax, because he was stressed, and the stress was likely to wear him down if he weren’t careful.

After he made this appeal, the two of them momentarily warmed to each other. Britannia sat closer and turned toward him. She eventually laid her head against his chest, wept, apologized. The world got quiet. All seemed resolved. My father smiled at the wall’s wood paneling. Then just as suddenly, Britannia raised her head and said what about her parents. They could take care of Jared in the mornings. They were retired. They would want to. This got my father angry again in a way he didn’t know he could be angry. He started raising his voice and in so many words put the kibosh on her idea, saying letting her parents look after Jared would send the wrong message. It would seem like he and Britannia couldn’t raise their own, and anyway her parents already looked down their noses at him. “Need I remind you of your mom’s attitude toward me? When we were first dating? What did she say? ‘Why don’t you find a man with a little money to his name? Why take up with some hellion from Dexter?’” Rather than address any of Britannia’s concerns, my father’s strategy was, as it would be with my mother, to browbeat with his own sorrows. However reluctant Britannia may have been to bend to my father’s desire, she nonetheless did, said all right, she agreed with him, he worked hard, she wanted him to keep doing what he was doing and to get the car-dealing business going.

2.

Days passed. Sunday morning. Jared had slept through the night. My father and Britannia had both been able to sleep in late. Britannia rolled over in bed, put her arm around my father, exhaled, smeared his chest hair, and said things had been going well lately, hadn’t they? He said yes, things had been going very well, they weren’t arguing or anything. She said there was a reason. She would tell him if he promised not to get angry. Then she confessed her secret arrangement. She had begun having her parents watch Jared some mornings so she could get some rest. Her parents’ house was just off Whiskville, on Catalina—incidentally, the same road my father’s future bride, my mother, grew up on. Catalina was a ten-minute walk at most from my father and Britannia’s mobile home at Fox Meadows. Despite the short walk, Britannia said she always strapped Jared into the car seat and drove over anyway, for safety. This news made my father irate. He started shouting and swearing, his head and chest grew hot, his body temperature rising to the point where he couldn’t think or talk sensibly. Instead of tackling the issue directly, he found himself complaining of wasted gas, Jimmy Carter, Aramco, the extra mileage she was putting on their second car. His shouting woke Jared. Outraged by Jared’s crying, he got dressed, packed personal items, got in the Camaro, and drove to his mother’s in Dexter, where he stayed for the next few days. During this period, he cooled down. He and Britannia exchanged calls. She apologized and said, “Bruce, come back.” He did.

Only Britannia’s drinking became bad. Before, she had drunk some spirits on special occasions, but this was different. My father got home from his shift, stripped, and carried his weary body into bed, bending toward Britannia, giving her a peck on the cheek. She reeked of beer. Though bothered, he feared confrontation. He wanted calm. But one morning, he broached the subject. She was shuffling off to the bathroom. He called out to her, which woke Jared. He asked her why she was getting drunk every night and waking up like this. She waved her arm and closed the door.

Instead of becoming angry at her, he grew fearful. She had a private world, and he didn’t belong to it. The thought was terrifying. Still, he needed to put his foot down. The closeted drinking had gone on long enough, he decided. He didn’t wait for a day off. While Britannia showered, he called into work and said he needed to use a sick day because of his boy. The foreman got on the phone after the secretary. He said my father had every right to use a day, but some advance notice would have been nice. My father asked how he ought to know in advance his son would be sick. Even though he was lying, he was indignant.

The foreman got him heated, so he went to Sammon’s bakery that morning and complained to his uncle. He complained about his wife’s drinking, too. His friends all nodded like they were listening to a sermon. Then my father went home.

Britannia said she was surprised to see him home, and so soon. Didn’t he have to work? A day off, he said. He watched TV, Columbo. He waited to talk to her, waited long—until after Britannia had run errands to pick up groceries, after she had made lunch and they had eaten together, after she had vacuumed and bathed Jared and put him to bed. Then he staged his intervention. It was still early evening, Jared asleep in his playpen in the middle of the living room. He and Britannia were seated on the sofa watching the TV. He gathered his gumption and turned to her and said that regarding the drinking he wanted to know what was going on and what was going on now. She admitted she had been doing a lot of solo drinking when he wasn’t around. He wasn’t around very much, she said. She felt lonely. He ignored the remark and said if she weren’t careful, she’d pass out drunk with their son in the bathtub. She might drown their son. Did she think about it at all? She said sorry. He asked about the contraband, the booze. While she went to the grocery store, he had gone through the cabinets and found a bottle of Ballantine’s someone at work had given him, but no beer, and it was beer he had smelled on her, he was sure of it. He had lifted the lid to the trash, found nothing. Where were all the spent bottles? Not bottles, she sighed, she didn’t drink from bottles. Cans. There was a system, she said, she had planned out long ago. In almost two years, didn’t he realize? There were lots of things he didn’t understand. As soon as he left the house, she had a girlfriend bring her over a six-pack, she said. My father asked what kind of beer she drank. She said Keystone. He asked what girlfriends she had who would bring her beer. She said an old girlfriend from high school, Theresa. He thought about it. He seemed to remember a Theresa. She said before he got home, she’d throw the cans in the communal dumpsters at the trailer park.

“Do you mean to tell me,” he asked, “if I were to go and look in there, I’d find your beer cans?”

“Good luck knowing mine from anyone else’s,” she said.

Jared stirred in his playpen, but neither of them worried, he would get back to sleep eventually. He had become a good sleeper, my father thought.

“There are lots of things about me you don’t understand,” Britannia said.

“Like what?” my father said.

“Like that I used to be a fun girl.”

He thought he had to smirk at that one.

Jared said da-da from his playpen.

Britannia stood up and towered over my father. “I was a wild one, too. I used to go out.”

“Is that so?”

She plucked at her T-shirt. “I used to get dressed up. Men liked me.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah. Do you think I didn’t have boyfriends before you?”

My father pulled her close. “Tell me about that.” He noticed she had gotten a permanent. He liked it. He had known her since their high-school homeroom. Back then, she wore her reading glasses on a string around her neck, but there in the living room, he saw her in a new light, alluring and strong-willed, a wife and mother who had already lived a richer life than most, not twenty-four and married with a child, a rarity more and more in the seventies, he thought (he was wrong about this; I looked it up: 1970s Americans’ median age for marriage was twenty-three). Apprised she had had this past life, he found her more attractive. The revelation of her drinking and the brief exchange that followed helped their relationship, at least as far as he was concerned. A fire that had been simmering had suddenly flamed up. He took to bragging to his friends and my great uncle, referring to Britannia as his “rowdy wife.” He said to Uncle James and company he had told her that while he didn’t like the drinking, she could drink two or three beers if she wanted to, but only a couple times a week. Only he had better not catch signs of her neglecting Jared or else the deal was off. His friends asked how she responded to the news. My father said she liked his assertiveness. How did she let him know that? Uncle James asked. “Let’s just put it this way,” my father said. “After I laid down the law, she took to me like flies at a picnic. About every night, we nearly shake the bed off its posts.”

3.

How long could the truth remain hidden?

One morning at the donut shop, he heard from his friends that Britannia had been spotted at Spider’s. My father knew the bar Spider’s, a glorified warehouse, really, out past the state line, where people went to drink and dance and rub against one another. My father’s friends said when he was working, his wife was going there and drinking and meeting men.

As much as possible, my father liked to think Britannia’s social life ended out of his range of vision. He didn’t want to think about her at a hole like Spider’s. Yes, he knew Spider’s, all right. He and Uncle James had gone there once after a car auction. No blacktop outside, only loose gravel, people parked wherever they wanted. Big red door bearing the name in white cursive, a logo of boxy dice beneath the cursive. The gilded doorknob rattled. Inside, no standing walls partitioned one section from the next. Bar flowed into dance hall flowed into billiard hall. Low spooky bulbs over the tables. Sawdust on the floor. The smell of old beer. That was where Britannia chose to spend her time.

That image alone had been enough to make the inside of my father’s mouth dry out, but his friend Shirrel had to open his big mouth. He said he had some news, then took a bite of a donut and let raspberry jelly plop down on wax paper. My father waited, tight-lipped, breathing through his nose, his hands shuffling, a pretense at looking loose, while beneath the table, he twisted one Reebok over the other. Shirrel said he had gotten a call from Dan Miller asking if he had heard what Bruce’s wife was up to and Shirrel had told him he hadn’t and Dan said he’d seen Bruce’s wife leave Spider’s with some man who wasn’t Bruce. My father turned dead-eyed.

He had to go to work that afternoon and do his overtime hours. As he grouped milk gallons and boxed them and pushed the boxes on to Loading, his mind wandered. The fantasy had gone bust. He had imagined his wife at home, suckling Jared at her breast, as dutiful as Mary to the messiah, afterward putting him in his mechanical swing so he could rock himself into a nap. Then she would make meals, eat, and wrap the remaining pots and dishes in tinfoil, including a plate for him. He knew some of this must have really been the case. The food, for instance. For nights he worked into the next morning, she had talked to him about preparing sack dinners he could carry with him. No, he’d said. For lunch, he might eat his meals with friends or take his meals alone, but for dinner, no matter how late he was, he wanted to be able to eat her homecooked meals. It was important to him. He thought it made her very happy. Now he guessed it made no difference.

Without thinking, he turned to his line partner and said, “Things are slow enough, cover my shift, family emergency,” and left.

Driving back, he thought he might catch Britannia in the act, that she might be at home with another man. He cut off the headlights and rolled into the gravel drive. He stepped in the front door. A chill hit him, like there hadn’t been heat on. The lights were off. From the bedroom, he heard a wail, Jared’s. He hurried to the back, half-expecting to find the house empty except for the baby, but there was Britannia, in bed, face up, mouth open, jeans, a sweater, and her sneakers still on, the playpen beside her, in which Jared bawled in the dark. My father picked him up. The baby needed changing. He carried Jared to the bathroom, removed his diaper, and cleaned him with the wet wipes, then he ran the bathwater until it was warm and roughly the height of a baby’s knee, and sat Jared down into the water and washed and shampooed him. This was the first time he had cleaned the baby, who, partially consoled, took breaks between bouts of crying. After a good towel-drying, my father carried Jared back to the bedroom where he fitted the baby into a diaper and some thick, warm pajamas that covered his body. Jared put his head against his father’s shoulder. Britannia was still asleep.

Even though my father had never called Britannia’s parents, despite their reservations toward him before the marriage, he knew they were good people at heart, though it pained him to think it so. He had no one else to contact. His own mother in Dexter would never answer the telephone past seven. Besides, they lived only a stone’s throw away on Catalina, in the better neighborhood, the suburban sprawl behind the trailer park. My father called. At nearly two in the morning, his father-in-law answered the phone. He didn’t ask questions when my father said he and Jared needed to come over.

His in-laws met him at the door. His mother-in-law took Jared. She got some baby food from the refrigerator—of course she had it on hand, Britannia had been dropping Jared off there some days, probably some nights, too—and fed him at the breakfast nook. My father sat down at the dining table. At the same time, on the corner of Catalina and Ridgewood, in a red brick house, my mother, a teenager unfamiliar with Bruce Pritchett, slept soundly in her bedroom. My father ate reheated leftovers.

The next morning, Britannia called and found out where they were. She came over. She sat down beside him at the dining table. He could have been there at the table all night. Britannia’s father had been eating scrambled eggs at the table. He took his plate into the living room. Britannia’s mother carried Jared to the den. My father bounced one caged hand against another, as though shuffling cards, and spoke low. “Jared had diarrhea down his leg. I can smell it on my shirt.”

“I don’t smell much better,” Britannia said.

“The smoking’s news to me.”

“Bruce—”

“Don’t Bruce me.”

“Can’t I go out?”

“And neglect our son?”

“You’re one to talk. Always at the donut shop.”

“Don’t turn this around on me. Where were you last night?”

“In bed.”

“Before.”

“What do you want to hear? If you know, why ask?”

Then and there, he knew they were finished. He wouldn’t ask if there were other men. He wouldn’t ask if any had come home with her or if she had gone home with them. Good God, he only hoped she never left Jared alone. He would have his future life to think about these matters. For now, he needed a new plan. He needed to move in with his mother. He figured that although Britannia would keep the trailer, she wouldn’t keep it for long and would eventually move back in with her parents, but fine, that was her decision. More immediately, he needed to contact his foreman. Britannia surprised my father by telling him his foreman had called and said my father was fired. He couldn’t just walk off on a shift like that, was what the foreman said. My father nodded. Britannia removed her Noah’s ark earrings and put them down on the dining table. They scraped against the lacquer. My father took her hand and held it, the softest he had ever felt.

4.

But this, my father said, was all in the past, back before he realized he even wanted to be a father. In divorce court, the judge ruled favorably for Britannia. She got primary custody of Jared. My father kept Jared on weekends—which didn’t amount to much time with his son, especially since my father had begun traveling cross-country from auction to auction selling cars. He had finally really got the car-dealing business going with Uncle James. And by then, my father had met a new woman: my mother. She mostly took care of Jared on weekends while my father worked. I wasn’t born yet. Five years after I came into the world, I learned of Jared. My mother had me on her lap in our living room, turning through a photo album. I came across a Polaroid of my mother seated on the same floor holding another small child in her lap. The two of them faced the camera, all smiles. “Who’s that?” I asked. “That’s Jared,” my mother replied, “your daddy’s other boy.” By then, Britannia had prohibited Jared from seeing my mother and father. My father said it was jealousy. I hadn’t been informed of this, but if I had, it wouldn’t have mattered. I looked at the carpet and pouted my lip. My mother’s hands came to my face. “Don’t cry,” she begged. I gathered up courage and said through drool, staccato, “I’ma gonna get my zizzors and cut his head off.” And then my mother giggled.

Three years ago, I got a call from my friend Stephanie saying my brother had died. I told her she must be mistaken; I had just spoken to my younger brother Jesse a couple days prior. But since I live halfway around the world from him in Korea, I thought it best to Skype him to check on him. Waiting for him to answer, I was genuinely scared. Jesse took the video call. I saw his face, wide like our father’s, and the interior of the family home behind him, the wood-paneled walls, the mounted deer head. He looked fine, everything fine. I explained to him I had gotten a call from a friend telling me my brother had died.

Jesse nodded and said it was our half-brother. Jared had been out back at the restaurant where he’d worked for twenty years when a food truck backed into him. The driver hadn’t seen him taking garbage to the dumpsters. I’ve lived through death before—my father and my mother’s, their different cancers. However, upon Jared’s passing, some special connection had been severed, a direct line I had to him I didn’t know existed.

My father introduced me to Jared once. In the worst possible way. After several years of never knowing what my grown half-brother looked like, I, a high schooler, came home one Saturday afternoon from my shift at a restaurant washing dishes, and as I entered the front door of the family home, I saw someone seated by the door, a rale-thin bald man in a baseball cap with a gaunt pale jaw, smoothly shaven except for the narrow mustache above his lip, and he wore eyeglasses like me. “Do you know who that is?” my father said from the sofa. I shook my head. “That’s your brother Jared.” I feigned a smile and shook his hand, then excused myself, saying I had to change out of my damp work clothes. During my shower, I had a panic attack. I went to my bedroom and couldn’t go into the living room for upward of two hours for fear of seeing my father’s face in a stranger’s.

Hearing as a younger person of my father’s marriage to and divorce from Britannia, and their rearing of their son Jared, I thought it a fine story and my father a fine storyteller. Unlike me, my father didn’t get tongue-tied as soon as he opened his mouth. But like every storyteller, he was a liar. There was nothing exact about any of this. My father had had years to craft the tale he wanted to tell, years to practice the words on me in our drives on the outskirts of our little Kentucky town. By age eleven, I had grown familiar with his standard version, only he added a detail. He briefly introduced, and then just as promptly abandoned the topic of, another woman whom he had met and lived with during a period between his first wife and my mother. He had met this woman at the milk plant, he told me, as we crested the bend of Whiskville, off which stood the hill upon which sat the trailer park Fox Meadows, my father’s former mobile home nestled away somewhere up there on cinderblocks, amid the rows of sorrows. Kitana, he said, wore Dior. It had turned him on, he said. He finally understood the allure of perfume. Like some Arabian spice, he said. I didn’t doubt Kitana’s existence, but she didn’t fit into the pre-established timeline. My father supposedly had gotten fired and divorced virtually all in one go. When did he have time to live with, let alone date, another woman? There at age eleven, I asked my father if he’d gone out with Kitana while married to his first wife. His face lost the smirk of the upper hand, his perfume fetish evaporating from memory. He returned to facing the windshield with his natural, purse-lipped frown, his brown lips twisted, a dark knot on an old tree. A past life, he said.

Boat House I, Westerly Rhode Island by Willy Conley

Near Flood. Fiction

Shauna Shiff

The driveway had washed away again, leaving one treacherous path of mud alongside a sluice of running water. She knew, driving home and seeing the thin skim of brown coloring the bleached road, that it was her dirt spread onto Route 3, but still had not expected the damage the storm had caused. The last of the right side of her driveway had dissolved, and Allie cursed as her car plunged into a rut. She pressed down on the gas; her wheels teetering on the remaining crest of the driveway and gunned it. Rob had always reminded her, with growing derision, to drive slow in snow, in hazardous conditions. Well, he wasn’t here to criticize, so she pressed the pedal further, her tires spinning in protest.

Closer to the house, Allie was relieved to see that the driveway was waterlogged but intact. All was not lost. Something had to be done, sooner rather than later, but she refused to tally the cost now. Since she had bought this house, her house, hers and Jemma’s alone, it had been one expense after another that she couldn’t afford, all shuffling to the forefront of the queue based on what failed that week. She knew of course, even without Rob there to tell her, that this house would be a money pit. Never buy a Victorian, he had always said. But Victorians had always been her favorite, and this one sat back from the road, close to the bay. With the windows open, you could hear the lap of the waves and smell the saltwater brine.

Allie had gotten home before Jemma. Her bus was due soon, and tonight Simone would be with her. Allie was glad that Jemma had a friend. The past few years had been full of worry about her daughter, who seemed too alone, so alone that she didn’t even know to be unhappy about it. But this year Simone had moved to Maine from Louisiana, and she and Jemma became inseparable. The bookish girl that Allie had raised was almost unrecognizable now that she had a friend. Jemma had adopted Simone’s preference for short skirts and fishnet tights, heavy mascara, and winged eyeliner. When Rob had mentioned this change to Allie, she had snapped, aren’t teenagers supposed to experiment? She said she thought Jemma’s new look was edgy. Of course, Allie didn’t think that, but she wasn’t going to share her fears with Rob. As far as he needed to know, she was doing just fine on her own.

She heard the girls shrieking and went to the living room window. It was still raining, not as hard as earlier today, but enough to still drench. Both girls were leaping to avoid puddles, spindly black-clad gazelles. Simone was charging ahead, and before she reached the front steps, she twirled, arms open, head thrown back and tongue pushed out. She was splattered in mud, her eyes screwed shut, spinning faster and faster. Jemma finally caught up and bent over in hysterical laughter, nearly throwing her backpack over her head with the suddenness of how quick she dropped. The girls stayed out in the rain, seeming to relish the bad weather. Watching them, Allie was tempted to fling open the door and scold them inside, but instead, she stayed behind the curtain, watching her daughter dance in circles around her new friend. Simone stayed in one spot, arms upraised, her mouth moving fast as if chanting. Her words ignited Jemma and as if bound to a tether, Jemma lifted her bony knees high in euphoria, twirling with abandon, circling Simone as if she were a maypole.

This was a new Jemma she was seeing, and Allie felt worry root. Maybe Rob was right; Jemma was a follower like Rob had always told Allie that she was, susceptible to aligning herself with bad leadership. Jemma did seem to worship Simone. But didn’t all teenage girls feel a devotion to their friends that bordered on obsession? Simone did fit what Rob would label a bad seed. Half her head was dyed an unnatural magenta, the other half black, and worst, she looked you directly in the eye when speaking to you as if she wasn’t afraid of anything. Such confidence was incomprehensible to Allie, and to her, Simone seemed narcissistic, capable of luring Jemma away. Outside, Simone had dropped her arms and Jemma rushed into Simone, nearly bowling her over with her embrace. Allie stepped back quickly as the girls turned towards the house.

“Mo-om,” Jemma said, when she finally came in, shaking water off like a too-big puppy, “The driveway is like, totally gone.”

“Not totally!” Allie always felt a rush to defend the house.

“Three-quarters to totally,” Simone deadpanned. “Anyways, you should see the shithole I live in.”

Jemma giggled and darted her eyes to Allie, gauging her reaction. Allie had to work to keep her face neutral. She was shocked at Simone cursing in front of her, but more than that, offended. This was not a shithole. This was a Victorian.

Allie thought that when it came to teenagers, it was good policy to not fan flames. So, she changed the subject, “I’m making pizza. I’ll call you when it’s time to put toppings on.” She wanted to lick her fingers and rub off the rivulets of mascara running down Jemma’s cheeks, but instead, she said, “Take off your shoes too! You guys are covered in mud and it’s dripping.”

“Like I told you, the driveway!” Jemma said, using the heel of one toe to slide her shoe off without unlacing, smearing mud into the grooves of the wood floor.

“Let’s go,” Simone said with authority, and the two bounded up the stairs, their steps in unison, heads bent towards one another. Allie rested one hand on the banister, watching her daughter disappear.

Allie sank into the couch, then sprang up just as quickly, remembering the bottle of wine prechilled in the refrigerator. One glass to settle the unease she felt – likely from the impending bill her driveway would be. But Jemma too. It used to be that Jemma would talk to her – maybe not about school or friends, but movies at least. In truth, Allie felt a little lonely without Jemma’s company. Twirling her wine stem, she wondered what the appeal of dancing in the rain had for Jemma. It wasn’t the splashing puddles that had excited her as a toddler, this was almost as if she and Simone were celebrating the rain. Almost like communing.

Draining the last of her glass, Allie shook her head free of such thoughts and set to work on dinner. The wine hadn’t eased her anxiety; if anything, she felt fuzzy detachment from the alcohol. She began to knead the dough, too aggressively, stretching with her fingers till she tore holes and had to start over. The kitchen looked out into the backyard, a reclusive spot shaded by trees, though the view was blurred by the rain. Off the kitchen door, a small patio, then, where the grass petered out was a well-worn path that led to the bay. When Allie and Jemma first moved here, they would walk down to the rocky beach every day, sometimes more than once. The ocean was always changing. Allie especially loved the unapologetic surge and swell of incoming high tide, but the low tide that unearthed silt full of snails, starfish, sea glass was Jemma’s favorite. In her bedroom, she had a glass jar filled with treasures found beachcombing.

A crash, followed by the sound of objects spilling and rolling across the floor above, startled Allie. Her first thought – which she resented herself for! – was to call out for Rob. Rob always solved all problems, investigated all sounds, soothed Allie’s worries. Eventually, though Rob, practical Rob, had run out of steam examining the minute strands of Allie’s fear. Allie had worked to overcome her anxiety without his guiding logical judgment. Rinsing her hands to remove the sticky traces of dough, Allie intended to go speak to Jemma. She was glad Jemma had a friend, she was, but they needn’t be so wild. Rob had always been the one concerned with decorum, and she could hear his voice in her head, chastising Jemma to be more careful. Allie wouldn’t admonish as Rob would have; she’d just ask them to calm down.

Allie resolutely climbed the stairs, feeling her anger toward Jemma rise. She hadn’t bothered to switch on any lights, leaving the upstairs shadowed. How could she even see? What were they doing together in the dark? Halfway up the stairwell, a loud crack of lightning illuminated the living room below. The lights snapped off, along with the electric hum of the refrigerator. It never got less eerie, the loss of power, how used you were to the safe buzz of electricity, and how alone you felt in the sudden quiet. Allie gripped the banister, counting the seconds till she heard the roar of thunder as she had as a child. She got to four when the boom shook the windowpanes. That was close. The storm was nearby.

In times like this, Rob would charge into action, lighting candles and flicking on flashlights from the emergency cupboard. Allie didn’t have an emergency cupboard, so she stood, uncertain, thinking about when she last used candles and if there were any matches. She remembered using a Citronella candle on the patio to deter mosquitoes. Maybe it was still there? She turned, walking cautiously down the stairs, unsure of her footing in the dark. She felt her way to the kitchen, hands out, dragging her fingers against the walls to align her. Reaching the kitchen door, she opened it to the pelt of the rain and stepped out onto the slick concrete in bare feet. The candle was there, a large jar with a double wick, filled with rainwater. It would be impossible to light wet. If only she had brought it inside. Rob would describe this as a preventable accident. If you just thought a little Allie, he always used to say, you could avoid reacting.

Dumping out the dregs of water, she made a plan to dry the wicks with paper towels. And she was sure the matches were still on the shelf beside the fireplace. Maybe she should start a fire – it was still storming and the temperature had dropped, cold and damp enough to warrant warmth. It could be cozy, she and the girls around the fire with peanut butter sandwiches. This could be just what she needed to resolve her concern over Jemma, over Simone.

More lightning flashed, followed quickly by a boom of thunder. Allie didn’t have time to count by she knew the storm was zeroing in on her house. God, her driveway would surely be washed away now. Allie, holding the candle upside down to drain out the dregs, turned to go inside when she heard a squeal. She turned and saw two figures run towards the bay. Was that the girls?