Full digital issue is below. Purchase print copy on our Blurb page.

From the Editor

An ice storm in March. Chandelier trees, glittering and clinking, broken branches crushed bushes, dangling power lines. I witnessed the aftermath but didn’t notice the storm. I knew it was sleeting outside, wet and horrible, but my thoughts were inside. I sat on the floor of my brother’s house drinking a canned cocktail. The house was full, my friends, some local, some visiting, my brother, his wife, their baby, my partner. We drank and distracted each other from six to ten. Finally, my brother deemed it bedtime.

Emerging from the house, I encountered the ice. The stairs were round with crystal, the branches moved too slowly in the wind. Heavy and fragile. In the car, we came upon a downed trunk that covered most of the asphalt. The upper stems scraped the side of the vehicle as we passed. Thousands of strings of rock candy, bumping and breaking against us.

I remember another ice storm. December 2008. My eleventh birthday. I woke, and the house was silent. The power was out. We sat in front of the woodstove, an iron leviathan, breath as loud as a coal engine. I sweated and waited for breakfast.

We walked the icy roads of rural New Hampshire, ducking twisted powerlines, hopping past falling branches. They shattered against the road. The winter sun was white and everywhere. Like a house of mirrors, it splintered through the forest, directionless, brighter than burning argon. I bumped a cluster of pine needle windchimes with my mitten.

Writing about New England makes me sentimental. It’s the setting of my childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, different at times, but always repeating itself. Every new thing that happens to me here feels like it’s happened before. Other people’s memories feel like they’re mine. Other people’s stories. Nonfiction and fiction alike. It’s the deciding factor: Do I remember this?

Thanks for coming back. I hope you remember the following.

J.B. Marlow

Contributors

Fiction

Nathaniel Krenkel (“Post Season Death Metal Romping”) hosts Rhizome Radio on WMPG, is a graduate of Bowdoin College, and co-runs the independent record labels Team Love and Oystertones. Krenkel’s poetry and prose have appeared most recently in The Sandy River Review, The Cafe Review, The Island Reader, Deadlands, Toasted Cheese, Chronogram, Bristol Noir, and Main Squeeze, and he is the publisher of the poetry-zine Foucault Hates Seatbelts. Krenkel lives in Portland, Maine with his family.

B.M. Hronich (“Streaks of Silver Lining”) is an undergraduate student at Rutgers University majoring in biology and minoring in creative writing, with aspirations of becoming both an author and a physician assistant. When she is not studying, she can be found writing, reading, and picking up shifts as an EMT. Her work has been seen in Footprints on Jupiter.

Matt Schairer (“Mr. Winslow”) is a lacrosse coach and college professor in Massachusetts where he lives with his wife and daughter. After years of moonlighting as a bass player and songwriter in bar bands, he decided to follow the money and start writing short fiction. His work has been previously published in the Shot Glass Journal from Muse Pie Press.

Robert McGuill’s (“Woke!”) work has appeared in Narrative, the Southwest Review, Louisiana Literature, American Fiction, the Saturday Evening Post and other publications. His stories have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize on five occasions, and short-listed for awards by, among others, Glimmer Train, the New Guard, Sequestrum Art & Literature, and Narrative.

Rowan MacDonald (“An Seanfhear ón Oileán”) lives in Tasmania with his dog, Rosie, who sits beside him for each word he writes. Those words have appeared in publications around the world, including Sans. PRESS, The Ocotillo Review, Sheepshead Review and OPEN: Journal of Arts and Letters. His short fiction was awarded the Kenan Ince Memorial Prize (2023).

Carl Lavigne (“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”) is from Georgia, Vermont. He holds an MFA from the University of Michigan. His work appears in LitHub, Hunger Mountain, Joyland, and other venues.

Benjamin Murray (“I Like my Parking Spot”) is a graduate of Eastern Washington University’s MFA program. In the summer, he enjoys roaming the woods of the PNW for Sasquatch and kayaking rivers. In the winter, he can be found on the mountains or on the ice with his beer league team. His work has been published or is forthcoming in Arkana, Cobalt, Rock & Sling, Pamplemousse, Sweet Tree Review, Stone Coast Review, River River, defunct, Rock Salt Journal, Construction Literary Magazine, and Southern Humanities Review, among others. His flash piece, “So, Coach Andrews Interrogates Me,” was shortlisted for Columbia Journal’s special edition on Uprising.

Devan Hawkins (“Ill-Equipped”) is a freelance writer from Massachusetts. His fiction has appeared in the Penn Review, Litro, and In Shades Magazine and his writing about travel, books, and politics has appeared in a number of places including The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, The Islamic Monthly, CounterPunch, and Matador Network.

Nonfiction

Jeffrey Scheuer (“Jane’s World: Encounters With a Nantucket Artist”) (www.jeffreyscheuer.com) is the author of two books on media and politics as well as "Inside the Liberal Arts: Critical Thinking and Citizenship" (2023). He lives in New York and West Tisbury, MA.

Visual

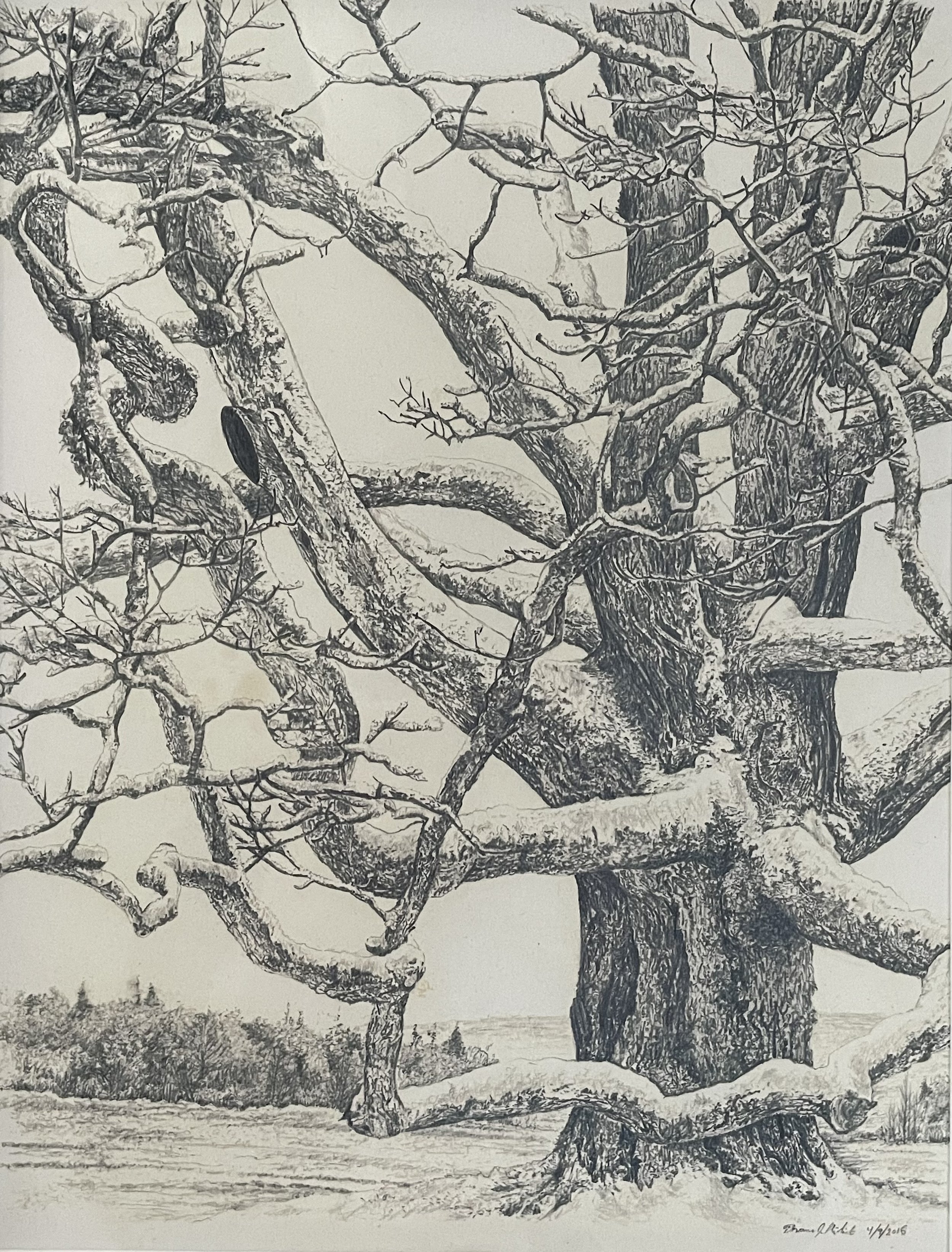

Thomas Philbrick (Cover: “Reflections 2”, “Bean Boots”, “Maple in Winter”, “Boats in Harbor”, “Isle”, and “Reflections” is a draftsman, writer, and composer living in Detroit, Michigan. His graphite artwork has twice been featured at the international art festival ArtPrize, as well as a variety of shows, exhibitions, and publications throughout the United States and the United Kingdom. His work highlights the subtlety and intimacy of the graphite medium by depicting moments of contemplation, introspection, and silence. His primary artistic influences are sculptor Alexander Stoddard, draftsman Jono Dry, and painter Carl Brenders. You can find more of his work on Instagram @philbrick_arts and on his website www.thomasphilbrick.com.

Post Season Death Metal Romping Fiction

Nathaniel Krenkel

“There’s a bunch of dead fish down there.”

“Where?”

“By the public dock.”

“Oh? why is…wait, do they smell?”

“Not really. Kind of. I didn’t really smell them.”

“I see you got some mud on your legs.”

“Yeah…Is it okay if I go back down there?”

“You were just there?”

“I know but…”

“Okay, that’s fine. But come home in about an hour if you want to go to the farm stand.”

“I will.”

“You have your watch?”

“I do…it’s…nine-thirty.”

“It’s ten-thirty.”

“Ten-thirty.”

“Be back by noon if you want to come. We’ll get some pumpkins.”

“Okay Mom. I definitely want a pumpkin, so don’t leave without me.”

“Have fun romping.”

Murph smiled at her mother, then hustled down the porch steps and across the lawn, stomping orange and yellow leaves. She slapped the wood plank of the rope swing as she passed the tall oak, stopped to look both ways, then sprinted across and down the narrow one-lane street toward the water.

As she ran past Ella’s house, she frowned. Ella’s old house. Ella had moved last year, out to a home not in the village.

Back before Ella was allowed to cross the street by herself, she would come up to the corner and stand by the fire hydrant. She would holler Murph’s name, and Murph would holler, “Mom, I’m going to go play with Ella.” Murph would then burst out of the house. “Sunscreen,” her mother would yell. “One sec,” Murph would call to Ella. She’d spin around and bound back up the porch steps. Quickly, she’d douse herself in SPF 50. “Bug spray,” her mother would add. Murph would scan the porch for the bug repellent. Spray one leg, then the other. Close her eyes and hold her breath; she’d make a cloud all around her, eyes closed, breath held. She’d toss the can of spray into the basket and bound again down the steps, pause at the street, then cross to Ella.

“Hi.”

“Want to do something?”

“Okay. Let’s go to Fairy Beach.”

“Let’s go.”

But now, as Murph ran past Ella’s old house, she felt the absence of her friend. Spontaneous romping was far better than a scheduled playdate. As she had tried to explain to her mother, romping cannot be planned. Playdates are what she did back home in the city. During the school year. Not on the island. Not in the village. In the village, she romped, under the public dock, around the rocks that formed the point next to Fairy Beach, she even romped as far as Gleem Knob and Melt Brook, now that she was a little older.

Murph reached the corner and turned onto Main Street. She ran past the post office, past the library, and farther up the hill; past the apple tree and the white picket fence. Mushy rotting apples littered the ground beneath the tree. She crossed the street and headed down the narrow, crumbling drive that led to Fairy Beach. Its real name was Ferry Landing Beach, but Murph preferred Fairy Beach, for obvious reasons.

She ran past an older boy, an island kid, avoiding his eyes. Ignoring him, mostly. She didn’t much care for the older boys, whether they be year-round residents or summer kids. They didn’t interest her. They were stupid. Not like, dumb. Just…pointless.

—

Seth walked past the girl and noticed she was taller, then he thought: perv. And then he thought, summer people, fuck’em. But no, she’s cool, she’s here at other times, like, she’s here now. Her family comes all times of year and her parents sit on the porch, reading, waving like robots, walking around with their stupid little dog. No, Seth thought, she’s okay. But also taller, and will probably be a babe in a few years, so you can just wait until then and not be such a perv. Then he grinned. But I am a perv, fuck yeah Satan rules eat a dick, then he stuck out his tongue and laughed at his own thoughts. Silly. He looked back, but the summer girl was gone. He fetched his Discman from his bag and put in a new CD.

Seth had recently gotten into death metal.

And doom metal and speed metal and grindcore and black metal and sludge and noise and deathcore and thrash and a bit of heavy prog. He was to the point where he thought, if asked, he could adequately answer the question as to what the difference is between…say…death metal and doom metal. Speed and drone. Slayer and Megadeth. Glam and trad? The OGs and the next wave? Pure noise? Was that a thing? Perhaps he didn’t know that much, in the big picture. The big picture of metal, a tree on-fire. It was all just words, why bother with that when the music was there to turn up and punch and get funny looks from the older guys in their trucks that only listen to sloppy country music which is basically just pop music about beer and date rape, that is, as far as Seth was concerned. Misogyny. That was a word he’d recently started using. Had learned it. He wasn’t entirely sure how he felt about the word. It confused him a little, made him feel defensive, but only sometimes. At other times it made him look at his friends in a different way. Even his dad. It stressed him out, really, when that happened. He thought again about metal. He owned only one Anthrax CD They were speed, and OGs, and cool as hell. He knew the CD he found on the for-sale shelf at the Camden Public Library was a score.

Then there was the CD he got in the mail recently, it was roaring and heavy, and like, much more obscure than Anthrax. There had to be kids out there…not on the island, probably not on any of the islands, but still kids out there someplace, definitely in Norway, or someplace, who knew more about this stuff, more about heavy stuff that made the world feel explorable.

More about metal.

Kids who got it.

His friends here, with their Imagined Dragons and Posty and Chainsmokers playlists, they had been bumming him out, and he knew he needed something other; then he found that book in the library, in the LOL the arts section, that book on the kids in Norway that made crazy metal and burned all the churches down and then one guy put a knife into another kid’s skull like on Walking Dead, and a singer of another band just went and did like that blonde guy, the with-the-lights-out-it’s-less-dangerous guy: BOOM. Shotgun. Kurt Co…something. His wife found him, Madonna, or Madonna’s sister maybe. Blonde, old. In Norway the dude’s bass player, or maybe he was just his friend, he found him after he’d shot himself in the head and like seriously, I shit you not, this is real, he took bits of the skull and brain and made ear rings out of it and…something caught Seth’s attention: a kid on an expensive-looking mountain bike was coming around the corner.

It was Josh. But whose bike was that? Seth quickly put on his headphones.

Josh stopped, “What you listening to?”

“Oh, hey Josh.”

“Hi. What are you listening to?”

“Oh, nothing. Pupil Slicer.”

“No way. For real? That’s a band?”

“Yeah, from France, I think. Or Russia.”

“Okay, sure.”

“What’s the deal with the bike?”

“It’s that kid Casey’s. Sweet, right?”

“Way sweet. Why are you getting to ride it?”

“He’s back for his granddad’s funeral.”

“Mr. Bath died?”

“Last week. Guess you didn’t hear?”

“No man, no. No one tells me shit.”

“Anyway, Mr. Bath, he had it in his will, or something, that he be buried up…you know, up on the hill there in that old graveyard by the landing strip. You’re parents aren’t there?”

“Don’t think so.”

“Lot of folks went.”

“Is he getting one of those tall tombstones?”

“I don’t know.”

Seth frowned. “They are so stupid.”

“What?”

“Those tall monuments in graveyards. The bigger ones. It’s like, yeah okay maybe for a few years you were the shit, but spending big bucks on a rock when fifty years later no one knows who the fuck you are anymore…that shit is stupid. Just get a normal sized stone. Don’t be such a dick. That’s all I’m saying.”

“Oh, is that all you’re saying? You’re high.”

“No I’m not,” Seth said, snapping at his friend.

“Where are you going, anyway?” Josh said.

“Nowhere. I was just listening to this band and walking. I saw that girl, the one that lives next to you.”

“That summer girl?”

“Yeah.”

“Murph.”

“Sure, whatever. I still don’t get why you’re riding that bike.”

“Casey said I could ride it. He can’t get dirty. Funeral.”

“Can I ride it?”

“No. Sorry.”

“Okay, maybe I’ll see you later.”

“See ya, Seth.”

—

Murph reached the end of the path that led down to the water and stepped with a crunch out onto the shells of Fairy Beach. A moment later, a picnic boat appeared from around the bend, where the rocks grew steep and plunged into the water. Most of the boats like this were already out of the water for the season, up in the boathouse yard.

The picnic boat was very close to the rocks, running parallel to the shore. In it were three men and a woman. They banked toward the center of the thoroughfare and looped around, making an arc, before vanishing back behind the rock point from which they’d originally emerged. Murph walked down to the water, her ear staying tuned to the picnic boat’s motor. Soon it was making the same close pass along the shore as it came into view a second time.

Murph scrunched her forehead. They must be trying to grab a mooring, she thought. Only, there are no moorings this close to the shore. Unless the tide is just super low right now. Murph scanned the shoreline. But the tide is not super low, she thought, in fact, it’s getting close to high. The boat shot past, pulled out away from shore again, and looped back to its starting point, like it was doing laps.

They didn’t see Murph and she started to climb the rocks.

There had to be something around the bend that she wasn’t seeing, something that was causing the boat to pass so close to the jagged shore. Maybe something had fallen overboard, and they’re trying to retrieve it. Like a life vest, or a cooler. Or a dog. Murph was scampering up the rock when the boat came around the bend for a third time, passing just below her. She was now a good twenty feet up on the side of the rock face. She held still. This time, the boat didn’t swing around but rather, followed the shore back toward the village. Murph watched as it slowed down at the public dock and dropped off two of its passengers.

Murph turned to the patch of water up ahead, the area that had been out of her view when the boat was making its loops. She stood up on the top of the small cliff and scanned the surface, eyeing a half-dozen moorings, each a good twenty feet from the shore. Much farther out than where the boat had been. Murph could see nothing to explain why the picnic boat had been repeatedly passing through this little stretch of water. It made no sense.

She heard the motor race and looked back over her shoulder. The picnic boat, now with a single passenger and a captain, was coming her way. But then it turned and slowed. The captain cut the motor and the small craft drifted up alongside a rowboat. The passenger grabbed the buoy and tied up. A minute later, the two men were rowing toward the dock. They didn’t see Murph up on the rocks. Whatever had been commanding their attention at the base of the cliff, it was now of so little concern that they didn’t even glance in her direction.

A mystery, thought Murph. She wanted to write it down. She sat on the rock and fetched her pen and notepad from her romping bag. She jotted down her thoughts, including: why would they risk hitting the rocks, coming in so close to shore, with the tide pushing them even closer toward danger? What was it? They weren’t trying to drop someone off. They weren’t trying to retrieve something overboard. Or maybe they were. Maybe the thing had sunk.

Murph put away her items and stood once again. She took a final look. Nothing sunk. Nothing broken on the rock.

A mystery, unsolved.

Hmph, Murph said aloud. She went back down to the beach. She picked up a fistful of shells and tossed them into the water. They fell like scattershot, making a delightful sound like stepping on bubble wrap or eating pop rocks. Then she spied a piece of green sea glass. She picked it up and rubbed spit on its sides. She put it in her pocket and moved on down the beach.

Ahead was the boy. His name popped into her head this time: Seth. She waved, but he either didn’t see her or was ignoring her. It looked like he was playing drums. He made tf-tf-tf sounds and bobbed his head. Whatever he was up to, she thought he looked pretty silly, playing his invisible drums, but she also liked that he was doing this despite looking silly. She wanted to ask him what he was doing, but before she got close enough, he turned away from the water and scurried up the side of the tree-filled slope.

She saw then he was wearing headphones.

—

Seth pulled his way up the steep incline, away from the shoreline. His feet slid on loose leaves and broken twigs, and he banged his knee on a rock. Stupid shit, he thought. Why are you going this way, anyway? Scared of that summer girl? Probably going to get ticks now. Ticks, Lyme, long Covid, the clap, AIDS, dick’s probably going to fall right the fuck off now, good job. He grabbed a branch and pulled himself up the slope until he came out on the cracked asphalt path that led down to the water. He turned the other way and walked to Main Street. The song he was listening to ended. He heard a honk, like an old-timey car, like a cartoon. But there was nothing there. Brain playing tricks. The next song began, crushing, drubbing, bald, scorched, unsafe. He thought about Mr. Bath. He drove an old-timey car. Down Main Street in the summers. He looked like a president, or a man who owned a factory. He’d honk and smile, wave, and putter. Cars lined up behind him because he was so slow, but Seth figured this was good because Mr. Bath was super old, he probably shouldn’t be driving at all. Crazy old…he might run over a kid and not even know it.

Or a dog…now Mr. Bath was gone and being buried.

Seth passed the post office and thought about going down to the boatyard. There were a ton of dead fish that had washed up in the night and were floating around by the public dock next to the gas pump. It was gross, but cool. His mom had said that morning that the fish probably died because someone had dumped a bunch of toxic something-or-other into the water, something they shouldn’t have dumped in there. Seth’s dad had told her to shut up, said the ocean was big enough for anyone to dump anything. He said the government cared more about whales than people. Seth had grabbed his Discman and left. He loved his Discman. Best find ever. Two bucks at the thrift store last summer. So much better than dumb Spotify which always cut out even with good wifi. Plus, he liked owning CDs. They were cheap, had no ads, and everywhere.

He turned onto the dirt driveway that led down to the dock. No one was around. Most folks not at the funeral were probably out hauling in their last traps. Lobster prices had been down. His dad had been in a shit mood because of this, but Seth’s dad was always pissed.

Seth reached the end of the dock and stood at the water. Hundreds of dead fish, floating and bobbing, staring single-eyed up at an autumn sky that was more white than blue. Seth’s eyes blurred at the carpet of rotting flesh. The CD ended. Darkthrone. Proper Satan-worshipping crazy-as-fuck music. He started to take off his daypack to find something new to listen to when he noticed the summer girl walking toward him. She came right up next to him and looked at the dead fish.

“What do you think caused it?” she said.

“I don’t know. Something spilled. Fuck if I know.”

“You’re Seth.”

“No shit.”

The girl frowned.

“Sorry,” Seth said. “You’re…?”

“Murph.”

“That’s right. Funny name.”

“It’s a nickname.”

“Right. That makes sense.”

“Does it?”

“You’re here for the funeral?” Seth asked.

“What funeral?”

“Mr. Bath.”

“Oh…no. I didn’t know…”

“Yeah. I guess he wanted to be buried here. If you have enough money, I guess even summer folk can be buried here.”

“I’d like to be buried here,” Murph said.

“Me too,” Seth said.

A bald eagle flew overhead. They both watched.

“It’s weird, it’s like town is deserted,” Murph said.

“It’s the funeral. But it always like this after y’all leave.”

“Does it?” Murph asked.

“Yup.”

“I feel like we’re the only two in town.”

“Only two in the whole fucking world,” Seth said.

“The whole. Fucking world,” Murph said.

They both watched the coating of dead fish. Neither spoke, but they both were grinning. In the thoroughfare, a lobster boat was coming in from the west, too fast, but no one was around to complain about the size of its wake.

“I better go,” Murph said.

“See ya.”

“See ya Seth.”

Murph turned and walked back up the dock. She started skipping before she reached the end. Seth watched her until she was gone. The fishing boat was now past, heading toward the eastern bay. Seth scanned the water for its approaching wake. Then he looked at the dead fish. He sat down on the dock and waited for the two to meet.

Bean Boots by Thomas Philbrick

Jane’s World: Encounters With a Nantucket Artist Nonfiction

Jeffrey Scheuer

I had never heard of the artist Jane Brewster Reid when I arrived on Nantucket in August 2018, crossing by ferry from Martha’s Vineyard. I was looking for artwork and antiques for the farmhouse I was renovating in West Tisbury, and Nantucket has more of both. But when I chanced upon one of Reid’s works at the Nantucket Antique Fair, it was love at first sight. I was determined to kidnap her back to the Vineyard.

The image that captivated me was a tiny watercolor of Sankaty Point Lighthouse at the eastern end of Nantucket, seemingly floating in midair above the dunes. It was signed in a minuscule hand: “J.B. Reid.” I learned to my dismay that it had just been sold, and went away that day empty-handed. But I was thrilled to have discovered Reid’s work, and anxious to learn more about her. Art – or so I told myself at the time – isn’t about conquest or connoisseurship, but about passion and the magic of such encounters. I had found love, and though the initial prize had eluded me, I would have to find a way to make the relationship work.

Back on Martha’s Vineyard, I did some research on the Internet, and soon discovered another Reid watercolor listed for sale by a different Nantucket dealer. The subject of this one was a barn surrounded by a dory and some barrels: a seemingly lifeless scene, but a beauty. It was identified as a “Nantucket scene, possibly Sconset.” This time I pounced, and I became a Reid collector.

Who was this woman whose brush I’d fallen for? Little is known about Jane Brewster Reid beyond some bare facts, gleaned mainly from dealers’ catalogues. She was born in Rochester, NY in 1862, apparently a Mayflower Brewster, and painted all her life. She may have begun visiting Nantucket as early as the 1890s; in 1902, some of her work was reproduced in a booklet by Henry S. Wyer titled “Sea-Girt Nantucket.”

Reid is also known to have visited and painted in England and Wales. According to Margaret Moore Booker (in the handsome volume “Picturing Nantucket,” edited by Michael Jehle), “Reid may have studied art in England, as her painting style is reminiscent of traditional English watercolorists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” At least one of her pieces was purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago. Nothing is known of her family, and I was unable to locate any photograph of her. It seems she never married, and she died in Rochester in 1966, age 104.

Reid was already in her sixties by the time the Nantucket Art Colony emerged in the 1920s, an informal group of mostly watercolorists that included a number of distinguished minor artists; its heyday was approximately 1920-1945. But she is listed among the thirty-odd members of the group in a digital retrospective exhibition mounted by the Nantucket Historical Society in 2007 (https://nha.org/ digitalexhibits/artistcolony/).

Most of the artists in the Colony were somewhat younger than Reid, having been born in the 1870s and 1880s. The group’s organizer, according to the Historical Society, was Florence Lang; the “dean” of the era’s Nantucket artists was Frank Swift Chase, who taught plein-air watercolor painting to Lang and others. Many members had studied at the Art Students League in New York, one of the first art schools to admit women. Most were summer visitors, although some settled on Nantucket; they included illustrators, art teachers, designers, and a few Brahmin New Englanders with names such as Folger, Saltonstall, Coffin, and Brewster – as in Jane Brewster Reid.

Further research turned up several dozen of her watercolors – most of them quiet, unpopulated Nantucket landscapes. Some are well-rendered but unremarkable pictures of rose-covered cottages and country lanes; one could imagine them adorning the quiet hallways of the island’s inns. Others, like the study of Sankaty Light and the barn-and-dory scene I had purchased, are more arresting. A few of Reid’s works depict girls at play on a beach, and display her talent; but she clearly preferred painting the island’s nature and architecture to portraying the human form.

Nearly two years after my discovery of Reid’s work, serendipity struck. The same dealer who had sold the Sankaty Point Light watercolor at the Antique Fair, minutes before my arrival, was now offering it again on the Internet. Had the previous buyer had a change of heart? I pounced, and the Reid watercolor I’d originally fallen in love with was finally mine – or so I believed. A likelier explanation, based on subsequent research, is that the artist sometimes did more than one painting of the same scene. No matter; the “Sankaty Light” watercolor – whether the one I’d originally seen or another – lit up my West Tisbury home.

As I continued to explore Reid’s work, one painting intrigued me more than any other. The online image was from a long-ago auction, and it depicted, with delicate clarity, a shipwreck on a Nantucket beach. The auction house had labeled it “Beached Three-Masted Ship.” The idea was hardly original; artists have long painted shipwrecks, and people have bought them – out of fascination and, perhaps, in homage to the nobility of human failure. But to my eye, Reid’s shipwreck scene was special.

Among other things, it brought back a vivid scene from my own childhood. In the early 1960s, as a boy of seven or eight, I’d been intrigued by the sight of a commercial fishing boat that had beached in a storm near Zack’s Cliffs in Gay Head (now Aquinnah) on Martha’s Vineyard. The empty boat lay on its side in the surf, a relic of a recent struggle with the sea. Perhaps it was my first recognition that adults don’t get everything right.

Decades later, I was awed by the maritime works of Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, and others that challenge the viewer’s sensibilities and sense of stability. (Homer and John Singer Sargent were two of the great American artists who inspired generations of painters, including most of the Nantucket Colony, to work in watercolor.) At the Old Tate Gallery in London, I encountered the watercolors of J.F.W. Turner, including scenes of storm-tossed ships in the English Channel that can almost induce seasickness. Disasters at sea are strange mirrors of our world gone awry. When vividly depicted, they can evoke pity, awe, and a sense of relief that we are merely spectators.

Reid’s shipwreck scene had a startling intensity, with a clarity in the brushwork that seemed to defy the prototypically blurry and impressionistic medium. Like the picture of Sankaty Point Light, it was strikingly minimal for a watercolor: the palette is limited, the composition mostly undefined sand and sky, with the beached ship at the center (her intact rigging exquisitely detailed) and brief renderings of dune and surf on either side. It called to mind the hypnotic poem by Robert Lowell, “The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket,” an homage to one of the poet’s relatives who was among the thousands of New Englanders lost at sea.

I kept the image of the wreck on my computer desktop, happy to be a digital collector but resigned to the fact that I would never see the original. I clicked on it often to refresh my memory of the haunting scene. The ship, as I learned, was the Canadian barque W.F. Marshall, a new cargo vessel of 945 tons, which foundered on Nantucket in March 1877, en route from Hampton Roads, Virginia to her home port of St. Johns, New Brunswick. She was listed as sailing “in ballast,” i.e., without cargo. The wreck occurred in a thick fog as the ship encountered breakers on the south side of Nantucket and was driven up onto the beach near Mioxes Pond. The spot where it happened is less than a mile from Bartlett Farm, where I first discovered Jane Brewster Reid at the Antique Fair.

Fortunately, all sixteen people on board the W.F. Marshall survived: the fourteen crewmen, and the wife and child of the steward, were rescued by personnel from the Surfside Life-saving Station. So was a black Labrador known as “Marshall the Sea Dog,” who later achieved some renown. (There’s a book titled “Marshall the Sea Dog: A History of Lifesaving and Notable Nantucket Sea Wrecks,” by Whitney Stewart, and an 8-minute video about Marshall the Sea Dog on the website of the Egan Maritime Institute (www.nantucketshipwreck.org/shipwreck/lifesaving-museum/ films.) Later attempts to salvage the W.F. Marshall were unsuccessful.

Reid, who would have been a teenager at the time of the wreck, must have painted the scene years later from a black-and-white photograph; yet her colors are subtle and radiant. Exactly when it was done, and how many other such scenes Reid painted in her long lifetime, are anyone’s guess. But the wreck of the “W.F. Marshall” is surely her most dramatic work.

In the summer of 2017, six years after discovering that elusive first watercolor, I returned to Nantucket. This time I flew over from the Vineyard, hoping to squeeze in a few extra hours at the Antique Fair before catching the ferry back in the afternoon. We circled for some time in a thick fog before finally landing, and I rushed over to the Nantucket Boys and Girls Club where the Fair was now being held.

As it turned out, I didn’t need the extra time. Within five minutes of entering the Fair, I was dumbstruck: there was the “Wreck of the W.F. Marshall,” hanging on a dealer’s wall. Without hesitation, I managed to squeak out the three loving words: “I’ll take it.” And after a quick tour of the rest of the show, I headed off to the ferry with another little beauty under my arm, spiriting it away to a new home on the Vineyard.

How to justify the crime? Well, I’m not a young man. And someday my three Reids (or Nereids – to me, they are sea nymphs of a kind) will return to their native island, still young and fresh, to be the envy of new eyes.

A lighthouse, a barn, a shipwreck: it’s hardly a vast collection. Yet in these and other works, the enigmatic Jane Brewster Reid rendered on paper what so many feel: a deep attachment to the New England coast, and to its architecture, artifacts, and traditions.

Like many artists, Reid never achieved prominence but occasionally outdid herself, displaying an exceptionally keen eye and delicate hand. Excellence doesn’t always equate with fame or sustained virtuosity. It’s where you find it. My sea nymphs, the products of a long but seemingly lonely and mostly forgotten life, evoke a place, an era – and the ineffable power of art.

Streaks of Silver Lining Fiction

B.M. Hronich

Broken wood is scattered across the floor, shreds of it splintering from each rod. I sit in the silence, arms tight around my curled legs, practically holding my breath. Red splotches saturate the grey couch fabric, oozing past every strand and fiber, the thick paint already beginning to dry. When Claude Monet was dissatisfied with his pieces, he obliterated them until they were remnants of another fruitless vision. Now, I’m surrounded by my own field of debris after having done the same.

The gallery is in two days, and I’ve completed all but one piece in my portfolio detailing the journey up a mountain. I talked to some other applicants, and someone is doing conflict and adversity, another is doing the loss of innocence. Climbing up a mountain is the best I could come up with. Applicants at my university enter a small portfolio of five to ten pieces on a specific theme. They’ll be on display at the art museum and a small banquet will be held, honoring the three best students with a free year of school.

I can take no more than five minutes trying to ground myself. When Brynn gets home, she’ll say it’s fine, that she knows the chaos is part of the process, but her weary smile and the way her bright auburn hair will stand on end is going to say otherwise. Although she won’t scream at me for the mess like I deserve, I adore her too much to do that to her.

I disappear in my room for hours. Around ten-o-clock, I hear Brynn blasting music in her bedroom as she hums along, and I know she’s getting ready to go out. I take another sip of the coffee I brewed. I start a new sketch, but my hand trembles over the canvas. Where I intended straight, even lines, there are scratches of lead, crooked and uneven. I slam both of them down. For a moment, Brynn’s music pauses, but then it continues.

At some point, fatigue weighs on my eyelids like dumbbells, and it becomes harder to fight them fluttering to a close. I climb into bed, pulling the soft white covers over my tired body. Just five minutes to rest my eyes: I set a timer and everything. But then when it finally rings, I shut my phone completely off, and I don’t wake until the daylight leaks through my blinds the next morning.

My blood turns cold as soon as I pick up my phone and see the date on my lock screen. It is officially the due date. My portfolio has to be at the museum by seven-o-clock tonight, and I still don’t have the last piece. I miss my ten-o-clock class, desperate to finish something. I flip through my sketchbooks, collages, books and magazines on art history, desperate for something that will spark a cascade of ideas in my tired mind.

In The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron writes that the best art is that produced when channeling The Creator (substitute God, the universe, etc.), and the art that falls short derives from the scraps of our mediocre human brains. So, where is He? I’d love to sit around and wait for Him, but I don’t think the museum would be open to conforming to His timing. Frustration mounts inside of me, the tension a thickening knot in my chest, dry eyes in need of tears to expel. I need the scholarship: I need the money, I need the award on my resume, I don’t have anything to make me stand out to grad schools.

I quickly wash up and change, throwing on a sweater, sweatpants, and UGGs. I take a walk downtown, away from campus, away from the expectations and deadlines, the crushing weight of it all. I put my cream headset over my ears, blasting music with hopes of emotionally escaping, replaying Living Breathing by Mesita. I feel like I float off the sidewalk with each strum of the guitar, each note in the piano’s melody. Slowly, the world is piecing back together, each fractal shifting into place, the margins no longer dissolved like Elena Ferrante wrote in My Brilliant Friend.

I pick up my pace as I approach The Book Burrow, the best bookstore known to existence. Vines climb up the front and curl around the sign of the dark brick building, short leaves blossoming from the stems. Short, plump pumpkins are arranged under the white windowsill beside the front door, the glass partially cascaded by looming tree branches boasting a mosaic of fiery red and orange leaves. I walk in, the bell chiming as I open the front door. The girl behind the counter smiles and waves to me, and I return the gesture, after seeing her here so many times.

I make my way over to the poetry section, my fingers gliding over each of the spines. I settle on one of the thinner ones, with a woven violet cover. I collapse onto the same plush grey couch, stretching my legs over the length of it, since there are only a handful of other people here wandering around the bookshelves. I take my time with each poem, digesting each word, desperate for the solace of a short break, but also for answers. And then I freeze, rereading one over and over again.

—

Your ‘no’ is merely a pause,

a breath held

before your next triumph awaits.

–you are a metamorphoses of your past resiliencies

—

That’s what this scholarship has the chance to be–that’s what I need it to be. And a spark lights inside of me, ideas flickering through my thought space, the surge of artistry I was hoping for. The stream of consciousness that Julia Cameron spoke of, I find it in each syllable. I think of my mountains, of each shifting scene lifting to the top. I close the book and rush home.

—

Around lunchtime, I go into the kitchen to fix myself a snack and see Brynn sprawled across the couch, reading.

“Any progress?” she asks me.

A smile tugs at my lips. “I think I tied it all together.”

—

In the late afternoon, I rush across campus to the museum, sweat beading across my forehead. The gallery is tomorrow night. I only have a little more than twenty four hours before I know what the judges thought of my portfolio, and I need the time separating me and that answer to dissolve. I walk to a cafe to study, hoping the evening will fly by until I go to bed and I pass by eight hours while I sleep.

It doesn’t.

Brynn and I don’t have classes the next morning since it’s Friday. I constantly check the time, only for minutes to be going by, rather than hours. A thick rope is knotted in my chest, and every time I check the clock, it’s like it only grows, pulling tighter and tighter. Reading and studying usually make the day fly by, but I can’t focus. Instead, I nag Brynn. She laughs, but I catch a glimpse of the mounting frustration starting to grow within her. Before she boils over, I leave to go on a walk. I trail through the old part of campus, past dated stone buildings t, across trails splitting lawns of trimmed grass and a group of boys passing a soccer ball, fall foliage embellishing the scene. I start down the gravel walkway back home.

At the center of classmates shuffling past, some hurried, others slow, clutching their backpacks and phones I find him floating on the air he strides through. Ruby and burnt orange leaves swirl in the shadows of his footsteps, and I watch him shiver as he shoves his hands in the pockets of his deep mahogany flannel. We had plans to see each other later, but here he is. His gaze is set in front of him, lost in the world his airpods transport him to.

“Carter!” I say, but he doesn’t flinch, and just as he’s about to brush by me, my fingertips graze the soft sleeve of his shirt, and his eyes widen, free from his trance.

He pauses whatever song he’s playing, and his soft eyes fall on me. He offers me a small wave, and when I realize he’s not going to stop, I change directions and walk beside him.

“What are you up to?” I ask him.

I watch his thumb slide over the screen of his phone and pause the song again. She’s Just a Friend by Cardinal Bloom.

“Econ,” he tells me. His face is as plain as his voice, void of emotion.

I nod. “Are you still coming tonight?”

“Yeah. What time did you guys want to leave?”

The schedule unfolds in my mind. “Me and Brynn were going to start walking down at six.”

As long as he gets there by six, we’ll be able to hang out for a bit and definitely leave by six-ten, and still get there ten minutes before the event starts at six-thirty.

“Alright,” Carter says. He stops in his tracks and I realize we’re standing before one of the tall, older buildings with faded bricks and stained window frames. Lofty trees with bright leaves line this row of buildings, and it casts a shadow over us. “This is my building. I’ll see you later.” There’s a tug at his lips as he says bye to me, a gentle Carter smile, and I’m able to let out a breath because it’s the smallest bit of relief I need that he actually wants to go. I think about his eagerness and giddy nature as a child. I imagine the years following since I saw him last at thirteen, chipping away at the boy I knew more and more, until only his dull undertones were left. But once in a while, there in the sparkle of his bright cerulean eyes, or in the shallow depths a smirk much like now, I manage to catch a glimpse of him.

By the time I get home, Brynn is gone. I imagine her having gone off to the library or somewhere else where the sound of my voice won’t make her want to rip her hair out. I collapse onto the couch in her place and check the time. It’s hardly been half an hour. I make myself food, watch a show, and when I realize only an hour and a half has passed, I do it over again. I need the hours to pass, to fast forward to tonight, but the more I check the time, the more it seems to stall.

Once four-thirty rolls around, I decide I’m going to get ready an hour and a half early. I blast music, hum and belt out the notes even though Brynn’s not here to join me. I pull my outfit out of the closet, one that’s been planned for about a week now, and put it on. I smooth down my skirt as my eyes trickle up and down my reflection in the mirror. It’s the tight black one with the small slit on the side, along with tights, a form-fitting white sweater with a sweetheart neckline, and Doc Martens. It’s flattering enough without bordering on slutty. With my hair blown out and natural makeup on, I put on small gold hoops and a dainty necklace with a small heart pendant and study myself. I decide it’s the best I’m going to get myself to look, and just in time, because Carter texts me that he’s here.

I practically fly out of my bedroom, almost missing Brynn sitting on the couch in that flowy white dress she likes. I didn’t even realize she was back. I spit out a compliment, because aside from the fact that I do adore her and I’m grateful that she’s coming, she really does look beautiful. I swallow hard and pull the front door open. Somewhere in the few seconds between, I catch a glimpse of Brynn raising her eyebrows.

For a second Carter’s eyes flash open, like his dark, heavy lids found a new breadth of life. For that brief moment I study him, the bright shades of blue swimming in his irises, blended in motion, the ombre smooth like that of an oil painting. I like to think that it was at the sight of me–not at the fact that the door before him was thrown open like I was escaping a fire inside. But then his eyes soften, and I find myself face to face with that sweet Carter smile again. His broad shoulders and thick arms fill out his white collared shirt, and I try not to make it too obvious that I’m paying attention to that sort of thing.

And that’s when my eyes fall to his hands, and before me he holds out a small bunch of white daisies. The roots are sprawled below the stems, dirt sprinkling onto the floor. The flowers are bright, aside from the one that droops to the side.

“Where’d you get these?” I let out a chuckle and accept them from him.

“I was in a bit of a time crunch, but I figured I should be getting you something, and I saw these out front.”

“What a gentleman,” Brynn nags from the couch, “You shouldn’t have.”

He tilts his head and gives her a look. Grinning, but silently screaming, Shut up.

The walk across campus to the museum feels like an instant, like I got so lost in the endless whirlwind of my mind that I teleported straight there from the apartment. One of the faculty members shows us where everything is and leads us to the display of my portfolio.

I notice the other applicants standing beside their row of canvases, the bouquets of flowers their families hand them, the crowds of friends flocked around them to show their support, but shortly afterward, my eyes float past their scenes, settling on my own. I fixate on my six pieces, on Carter and Brynn in their best dress, and a warmness grows inside of me as I watch them study my artwork.

“Looks good,” Carter says, “Mountains.”

“So are you going to interpret the deep philosophical meaning behind them?” Brynn asks, “Ooh–and I want to see what you did with the last one–” Just as she starts to look over at the last canvas in the line, I step in front of her.

“I’d rather walk you through it,” I say.

At a glance, there isn’t anything extraordinary about the first five paintings. I give them each their respective attention, talking about the different scenes. The subject in the piece starts at the bottom of the mountain in the first painting, and gradually advances upwards as the pieces progress. At the bottom, it looks much like now, a mosaic of autumn foliage among luscious trees, the leaves scattered about the trail the subject climbs. There’s a common warm tone to the paints I chose. Along the way, the shifts are slight, but there, the phases of her journey alter with each milestone. The vegetation shifts from autumn to that of spring, winter and summer, along with the tones, strokes, and styles. The muse of one is clearly Impressionistic, another showcases my admiration for Romanticism.

We get to the sixth one, and it silences Carter and Brynn. They don’t Hmm, and Wow, and shower me in compliments like they did for the others. I watch them try to comprehend it, the squinting of their eyes, the twitching of their lips and eyebrows.

I suck in a breath. “And at the end of the journey up the mountain, there is metamorphosis,” I say.

We all look at the subject in the piece. Where her arm extends and her finger points, stems twirl and a bright flower grows. Something like wings sprout from her back, melding into the arrays of trees. She herself is blending into the world around her, morphing with the better parts of the forest into a unique beauty that’s all her own.

“It’s–incredible,” Carter manages.

Fireworks explode inside of me. Really?

“Yeah, really.” Brynn throws her arms around me. “Ugh–I’m just so proud of you,” she takes my arms in hers, “This scholarship is yours. My best friend is an artist!” she squeals.

We wander around the showroom, making small talk with the other applicants, allowing ourselves to savor the refreshments until the banquet dinner. I shove the hot penne vodka down my throat, chasing it with bread and salad. I want to finish eating, for everyone around me to finish, too, so it’ll be time for them to announce the recipients. Somewhere along the way of complaining to Carter and Brynn about how long they’re taking, a short man with glasses and sparse white hair in a heather grey tux shuffles to the front.

I suck in a breath, grasping onto both of their wrists despite them being mid-bite. “It’s happening,” I gasp.

They both chuckle, but I don’t think they realize I’m not joking.

“Always so dramatic,” Carter says.

The professor announces the recipients one by one. With each name he declares, I clutch tighter onto the white tablecloth, waiting for my name to be next.

But it doesn’t come.

I feel my entire body melting into these polished hardwood floors amidst the winners and other losers, slipping beneath the cracks of the front door, until I’m sliding down the street and into the gutter among the sewer dump, where I belong.

I fix my vision on the tablecloth I’m clutching and twirling in knots. Out of the corner of my eye, I see the two of them glaring at me, and I can’t face them. Right now, I want to be anywhere but here.

“Those who entered their portfolios for the scholarship gallery were also entered for the Artists Across Europe program. The five students selected for the program will be offered the opportunity to spend their spring semester studying abroad across Europe, with tuition and fees matched to that of their fall term bill, along with an additional five thousand dollar scholarship.”

I slump in my chair, my phone between my knees so I can scroll through Instagram without it being too obvious. The professor rallies off names. One by one, I can hear students rising from various points in the crowd and shuffling out of their seats, making their way up front to the makeshift stage before the applause softens and they collect their certificates.

And then it lulls, and Carter is nudging me, and I ignore him. Brynn slaps the side of my leg. “Go up there,” she says through gritted teeth.

I look up from my phone and blink. The entire crowd, the recipients on stage, they’re all staring at me. The professor studies me, gripping the microphone, clearly agitated, and although he’s a stout man, it’s like his gaze is burning holes through me.

I’m one of them?

I drop my phone on the chair, make my way to the front. My footsteps echo in the silence. The professor hands me a certificate, and I stand in line at the front, next to a boy with a bulky watch that glimmers bright enough in the stage lights to blind me. Just as they call the next name and attention is off me, I read the certificate in my hands. A smile creeps onto my lips, and my head feels light, my entire body, even, like the exhilaration is about to lift me off my feet. Europe has been on the Pinterest board since middle school. When I fantasized about my great European exploration, I always pictured myself far into my twenties, maybe even later, when I was completely independent, with a real job and the big girl money to do so. I never considered that it could be within reach this soon. I feel the heat oozing into my cheeks, and I know how rosy I’m turning. I’m going to Europe.

I find Carter and Brynn in the small crowd. Brynn’s smile is bright, her eyes twinkling from her seat. Carter’s is tender, warm like the fires we used to sit around as kids.

The boy beside me nudges me. He offers me a fist bump, whispers, “Nice job.” I catch him glancing at my certificate.

Carter, Brynn, and I find each other as soon as they finish announcing the recipients. They congratulate me, hug me, tell me I’m way better off with this experience than the original scholarship, and propose plans for dinner.

“Congratulations–Sage, right?” I turn, and it’s the same boy I stood beside.

I nod. “You too,” I say. I peer to his hand, catching a glimpse of his certificate. “Remy.”

Something like a blush simmers into his cheeks, and he smiles at me the way Brynn does. He’s wearing cream pants and a half-zip navy sweater, and with his perfectly parted blond hair and milky white teeth, he looks like a sculpture from the Renaissance. And he’s an artist? I study him. He’s gorgeous. It’s like Michelangelo came back from the dead and molded Remy’s face with his bare hands. I notice hints of dark roots that make it clear he’s a fake blonde, but it hardly matters. The wavy, golden strands suit him.

“You an art major too?” he asks me.

“Minor,” I say, “Psych major. I want to go into art therapy.”

Remy nods, considering this. “Nice,” he says, and then he smiles, “Well, I’m looking forward to getting to know you better in Europe.”

My heart clenches. “You too.”

And with that he saunters off, leaving a graceful stride and perfectly straight posture behind him, even as he pulls his phone out of his pocket and starts to tap through it. Mine buzzes in my hand, and I look down at the notification.

Remy Donato has requested to follow you.

I turn to face my friends again.

Excitement sparks across Brynn’s face.

Carter blinks. A pale, dull look envelops him.

Mr. Winslow Fiction

Matthew Schairer

Dear Mr. Winslow,

I hope this email finds you reasonably well, and I apologize for the apparent randomness of my request, but I must ask for your help in my search for a most important item. You see, my wife has misplaced a note, an important document is probably a better way to put it, and I have been entrusted, or more accurately enlisted, to retrieve it and bring it home in haste.

You may be wondering how this concerns you, Mr. Winslow, and you’d be well within your rights. The reason for this inquiry has to do with Little Free Libraries. Take a Book, Share a Book, yes? I know you are familiar. I imagine you have an idea where I am heading.

My wife encapsulated this most crucial file into the folds of a book, to be more specific, her favorite book, The Sound and The Fury by Faulkner. If you ask me, it’s a gluttonous waste of space on the bookshelf. I can never understand what he is saying, but I was just a science teacher for thirty-five years. I have no literary training. If it was up to me, I’d have put it in DeLillo. But my wife, although a fan of DeLillo, is a devotee of Faulkner. Indeed, she is almost unconscious in her attraction to Faulkner, like a stick swept into a rolling stream, and so, she has eleven or twelve copies of The Sound and The Fury floating around our house at any given time.

Yesterday, when she couldn’t find the document, she tore the house apart, shoes flying, manila folders flopped open on the crowded countertop, cheerios stuck to her socks. She eventually reasoned that the only place it could be is still in a copy of The Sound and The Fury, and she must have dropped this fated copy off at one of the Little Free Libraries. You would think it would be a simple enough solution, go to the Little Free Library (henceforth referred to as “LFL” for the sake of time), find the book, grab the important paper, and go. But herein lies the problem, Mr. Winslow, and you might know where I am going with this. My wife contains a compulsion, or better yet a propulsion, to visit as many LFLs as she can. Now that she is retired, it comprises the better part of her non-sleeping hours. She stops into a park, or a street corner, finds the LFL, browses through, takes a book, leaves a carefully curated volume that will fit the particular emotion, or, as the kids say, the vibe of the collection, and heads on her way. She considers it her own little mission, you see, to constantly improve the assemblage at each LFL, taking the offering with the weakest connection, and replacing it with a selection that ties the group together in better harmony.

So, clearly, it will be a challenge to find the correct location, but I like my wife to think of me as a practical man of the world, so when there is a problem that needs remedying, I steady my sights on solving it. I started with the LFL at the park in Plainville, found another in a neighborhood off 106, stopped at the LFL outside the pizza place in Foxboro, and then circled back to the purple one on Madison Street in Wrentham. I’ll be honest, I am amazed at how many of these things there are out there. Unfortunately, I found but one copy of The Sound and The Fury in my travels, at Kelly’s Pizza LFL, and it contained no important documents within its worn pages. When I returned home this afternoon and told my wife of my travails, she sighed and said, “Yes, that makes sense. Kelly’s has been going through a bit of a modernist phase over the past month. I’m not surprised I left him there. I believe I took Pynchon, he was flapping his wings in everybody’s business.” A year or so ago, I would have taken her account of this LFL as gospel. Nowadays, sir, her memory is difficult to trust. We were hopeful for a while that it was just a reaction to the medicine, but it is clear now that it’s something worse.

Anyway, the reason I am writing you, my fearless friend, is because after she said all of this, her back went straight and her eyes jumped to the top of her head. “We need to find Francis Winslow. His book is in every LFL in the area. He is our best shot to find the note.” She sprinted out of the kitchen, socks slipping across the hardwood floor like a slalom skier, or more accurately, like a child in her first pair of skates on a freshly frozen pond. She returned from her study with four copies of your book, One More First Time.

As the day had waned considerably by that point, and in my advanced age I tend to feel the ever earlier pull of a late afternoon nap, I thought the most practical move I could make was to do some home research on this Francis Winslow fella. So, I read your work. I must say, Mr. Winslow, I was impressed. I found your protagonist, Phil, last name unclear, to be particularly compelling. I guess I would say that I liked the way he hated himself. His stepfather, if that’s what you’d call it, Captain, was a terrific delight as well, a cruel collage of misanthropy and libertinism. If you would indulge me, I especially liked the passage where Phil tells Captain of his friend who chefs in a hoity-toity restaurant and cannot eat contently anywhere else because he is poisoned by ambition, he can “only taste the mistakes”. I am not sure why, Mr. Winslow, but I found that paragraph refreshing. Maybe it shined a bit of light on my own vanity, but I am no literary critic, just a science teacher for thirty-five years, which I think I mentioned.

Anyway, to make a long story short, I finished your impressive story and followed up by spending over an hour on the web reviewing your site. What started as an investigation turned swiftly into a celebration. I wish you nothing but the best in your pursuit of literary fame and fortune. I know little of guerilla marketing and the work of the fine folks in the publishing industry, but I have to imagine there is a better strategy for placing your book into the hands of willing readers than dropping free copies off at every LFL in driving distance, but I guess this email exists as evidence directly in contrast to that piece of unsolicited advice.

I ask of you, Francis, if I may, only one thing. As you continue your mission throughout our great Commonwealth, inspecting each and every LFL to make sure they maintain your presence, please stop and look for copies of The Sound and The Fury. If you see one that contains a twice folded yellow paper with a scraggly list labeled “Amelia’s Last Dance: Things To Do Before This Bird Has Flew,” please call me at the number below. Time is of the essence.

Respectfully yours,

Paul

Maple in Winter by Thomas Philbrick

Woke! Fiction

Robert McGuill

When did I stop being the man I am, and become the man I was?

What part did I play in this tragi-farce called old age except the part every man plays, unwittingly, in his own demise? And why, why in the name of weeping Jesus did I not see it until now?

It took the headstone, I suppose. The marker with my name on it.

Intimations of immortality my ass!

When I ordered the tombstone I thought I was doing the right thing, making life easier for my kids. It was part of my pre-need estate strategy. I wanted to make certain no one mucked up my plans or took liberties with my after-death directives. But mostly I was trying to be responsible. Control the narrative, as we say these days. Leave my stamp on things.

I’d paid for the stone months ago. Back when the doctor told me I had less than a year to live. But the day I took the cab out to the monument shop to approve the finished engraving—no! The place was shuttered! Locked up stem to stern. Which left me standing there, like an idiot, staring through the chain link fence with my mouth hanging open and the cabbie shouting over the seat back through the door, asking me should he stick around?

There was a delinquency notice from the Department of Revenue just above the giant brass padlock that held the chains in place. A closure notice that hinted at financial improprieties. Delinquencies of one nature or another. There were handwritten notes stuck in the fence too, some on business cards, some on Post-It stickies, some on the backs of grocery lists and old receipts. Most of them from concerned customers inquiring after their property.

The headstone—my headstone—was on the other side of the wire barrier next to a stucco tool shed with a small, arched window that looked like it came from a child’s playhouse. It appeared quite natural sitting under the shade tree where the delivery service had left it. I could read my name chiseled in the polished black granite: THEODORE J. RENNY, Born 1954 – Died....

I shook the fence in mild protest. It rattled but there was nothing more to coax from it, and my empty hands fell clapping at my sides.

“Hey, pal,” the cabbie shouted, leaning across the seat back. “You want me to stick around or not?”

I waved him away, but he didn’t go.

“Yo,” he said, pointing to the meter with a polite shrug.

I pulled out my wallet and paid him. Then I started back toward the fence.

“Yo,” he said again, nodding at the cab’s back door, which I’d left open. “Mind?”

I walked over and shut it.

—

The engine rumbled and the tires spat gravel as the lumbering yellow vehicle sped away. I took the cabbie’s hasty departure as commentary on the gratuity I’d given him, which he apparently considered inadequate. But I had my own grievances, and as soon as he and his ugly yellow sedan were out of sight I set about trying to redress them.

The granite marker locked behind the gate was my only concern, and I was forced to accept that its impoundment was going to present me with a number of problems. The biggest of course was that I’d be dead in six months and, without a stone on my grave, or the credentials to pass into eternity, as lost as a lost soul could be.

The cemetery where I was to be buried, Mt. Evergreen, was across the street from the monument company. The plot I was to be buried in was on top of a hill, near a grove of honey locust trees that opened out onto a scenic view of the mountains. Like the headstone, the plot had already been paid for. Also part of my pre-burial planning.

The cemetery’s iron gates were open that morning, so I decided to drop by and see if someone in the front office might be able to shed light on the monument shop’s closure. I found the sexton standing outside the office with his hedge trimmers and decided he’d do. He wore dark glasses and a ball cap and had a sound-muffling headset yoked around his neck. He told me the owner of the monument company, Mr. Noah, had disappeared a week ago. He said he’d closed the doors, disconnected the phone, and vanished, his 100-year-old family-run business kaput overnight.

When I got home later that afternoon, I phoned the Better Business Bureau and inquired after the matter, hoping the sexton was mistaken. But the lady on the other end of the line painted an even bleaker picture. She said there was no guarantee of any resolution of the problem between Mr. Noah and the Department of Revenue, and that the impounded goods would remain under lock and key until the company either satisfied its debt or declared bankruptcy.

“You can file a complaint with us,” the woman told me before we hung up. “Or call the state district of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court and ask about your options. But that’s as much as I can tell you, given the circumstances.”

I expelled a heavy breath. Thanked her and put down the phone.

Six months ago my physician, Alexander Fleege, M.D. with the LaVita Group, informed me that my condition was terminal. He gave me a year to live, at the outside, but said he’d be surprised if the end didn’t come sooner. He didn’t mean to sound callous, he said, but my health history was sketchy, at best, and this wasn’t his first rodeo. He’d been at the oncology game a long time and well, there were days when you blew sunshine and there were days when it was just better to tell the truth.

Knowing what I knew—where I stood health-wise, and where I stood legally with my impounded headstone—I can’t say I was overly enthusiastic about the idea of waiting for the bankruptcy court to come to my rescue. Yet at the same time, I didn’t have much choice. The clock was running out, and the best I could do was cross my fingers and hope a quick verdict would remedy the injustice.

While I waited to hear from the courts, I made weekly visits to the monument shop. I’d turn up every Sunday and check to see that the stone was still there and that the gate was still padlocked, then I’d walk across the street to the cemetery and say hello to the sexton, whose name I learned was Peter (or maybe it was Perr), then walk up the hill and stand on my plot for a while and look out at the world and meditate. Peter (Perr) was always interested in my updates regarding the stone, and he often took time to brew a pot of coffee and chat with me about its involuntary confinement. We spent a good many hours together and got to be friends. I liked the kid, and tombstone notwithstanding, I was comforted knowing such a kind soul would be tidying up my own resting place someday.

Then something happened. Something quite odd.

As the weeks dragged on, my health began to show signs of improvement. I was still going to die, Dr. Fleege assured me, only not as soon as he’d originally predicted. He was embarrassed, I think, at having to revise his timetable and admit the possibility of being wrong. But he was, as he so often reminded me, a professional oncologist, and it was his job to keep me apprised of the situation, good or bad.

A new round of tests were ordered for my next appointment, and when they came in Dr. Fleege grudgingly admitted they looked even more encouraging than the previous set. It had only been two weeks since my last visit, but it appeared my life expectancy had doubled. I was going to live a year now, maybe longer.

“Don’t go getting cocky,” he warned me, removing his rubber gloves with a disdainful snap and tossing them into the biohazard container. “You’re still going to die, Ted. It’s not a matter of if, okay? It’s a matter of when.”

The medical people could call it what they wanted—luck, accident, divine intervention—I didn’t care. But I was on the road to wellness and there was nothing anyone could do about it. I didn’t mention the impounded headstone because I didn’t think Dr. Fleege would believe me. Yet I was certain it had everything to do with my miraculous recovery. When the monument shop closed, putting my future (and yes, my immortal soul) in limbo, my illness was arrested, too. The whole matter seemed improbable, a far-fetched speculation. Yet the way I saw it, as long as the stone marker was unable to find its way to my grave, the same might conceivably hold true for my body.

I was elated, of course, about the turn of events. I had an extra eighteen months or more in front of me. Maybe longer. But the mysterious one-eighty turnabout in my health seemed to exasperate everyone else I knew. Dr. Fleege, for instance, acted like a gambler chasing his losses. And my kids were even worse, treating my new lease on life as if it were somehow embarrassing, brought on by the commission of some masturbatory act.

“Are you sure you’re not dying?” my daughter Karen demanded in a scolding voice when she saw me. “What did Dr. Fleege tell you? Exactly.” She pressed her fists to her hips. “Did he give you a medical reason for the remission? Something useful? The hospice company is going to charge us, you know, if you decide you’re cured and you back out of the program. You can’t just come and go, willy-nilly, with people like that. Remember the forms we signed? The talks we had with that man, Mr. Cushing? They’re an outcome-based operation, Dad. They expect results.”

My son, Kevin, chimed in, looking to put his older sister in her place. Kevin had recently come to Jesus, and his interest in my resurgence was—how shall I say—more than just academic. He’d prayed over me numerous times since my diagnosis, and my recovery confirmed his belief in the healing power of faith. “Never mind Miss Smarty Pants, Dad,” he said. “What’s important here isn’t the hospice arrangement. It’s that you’re on the mend...with a chance to make peace with the Lord.” He smiled, a chilling Christian warmth flushing his face. “Praise God almighty and His son, our Lord Jesus Christ for this miracle of faith,” he said, closing his eyes and laying a sweaty hand on my head. “Thank you Jesus, in the name of the Father, for hearing the supplications of your humble servant, Kevin, whose most earnest prayer is, and ever shall be, to shepherd his father, Theodore, toward repentance and eternal salvation.”

“Jesus can stand in line,” Karen said hotly, turning to her brother. “Last time I checked, it’s me who’s doing all the work around here.” She glared at him, fuming. “Do you have any idea what these medical services run, you idiot? The man’s insurance is shit! He’s two full years from Medicare for Christ’s sake! I’m dealing with a $5000 deductible and a mountain of paperwork!”

Kevin frowned over a pair of thin pursed lips. The words stung, and an anguished look settled in his face. He didn’t like the idea that it was Karen who looked after the bills and groceries for me, taking all the credit for keeping my house in order, and he closed his eyes and folded his hands and whispered in a half-audible voice, “May the Lord in all his mercy damn you to hell, Karen.”

Their bickering went on and on like this. The same way it used to when they were kids. And as I watched them flail and shout and threaten one another over my quote-unquote well-being, I felt myself fading further into invisibility.

People had been looking through me for years, but I hadn’t recognized the extent of my transparency until I watched my children duke it out in the middle of my kitchen that day, shouting one another down in venomous voices, each pretending to know what was best for me.

“Stop it,” I said, pounding my fist on the table.

They looked at me. Surprised.

“Stop,” I said. “Stop what you’re doing and leave.”

They turned to one other, shocked. Flashes of recrimination lighting their eyes.

“Leave,” I said. “Now.”

I turned my gaze to the window. I couldn’t look at them anymore. I’d been given a life-saving reprieve, and neither of them was smart enough or selfless enough to see it. Their mother would have been horrified. Her own offspring! Thank god we decided to quit at two! A month ago I was a condemned man, but now, by some miracle of mysterious origin, my death sentence had been lifted, my execution stayed. I was woke, as the man in the penguin suit said on TV the other night during the Academy Awards. I was present. I’d been given a glimpse of a world I’d forgotten about long ago, and my eyes had been opened to possibilities I’d never dreamed.

I scrounged up a pen and paper. Began writing down all the things I intended to do with my newfound freedom. All the things my early onset invisibility had precluded me from doing in the past. I’d learned a lot listening to people I didn’t know, or like, tell me how my life should, or would, play out. And now I intended to make the most of that knowledge—by ignoring it. I had a future again, and what that future did not include was illness, suffering, or death by anonymity.

“How do you feel?” Dr. Fleege asked at my next appointment.

“Relevant,” I said.

He looked at me, suspiciously.

“Any changes in your medications since your last visit? Any lifestyle changes I should know about?”

I shrugged. “I took up smoking.”

He stopped what he was doing and stared at me, incredulous. “What?”

“I took up smoking.”

He hung his head. “Jesus, Ted.” He looked at me from under a pair of heavy gray brows and implored me to tell him I was lying. “You’re busting my balls, right? Please. Tell me you’re busting my balls.”

I took off my shirt and laid it on the examination table. Flexed my arms and sucked in a deep, satisfying breath. “Camel straights,” I told him, slapping my pecs. “A pack a day.”

He threw up his hands demanding to know why, in God’s name, I would make such a self-destructive choice when it was a proven fact cigarettes kill.

“Because I felt like it,” I said.

“You felt like it.”

“Yeah.”

For once in his life my esteemed oncologist didn’t know what to say. He apparently forgot I was living on borrowed time—time brokered by no one other than himself, the professional MD whose first rodeo was not me—and it must have also escaped his ivy-league memory that it was his diagnosis of less than a year ago that set me on the path to the cemetery. If anyone deserved to act gob-smacked, it was me. The fact that I’d found a way to dodge death was a one in a million shot, and if it annoyed him, too bad. From here on in I was going to do anything and everything I wanted, even if no one else agreed with it. Especially if no one else agreed with it.

“Smoking’s a filthy habit, Ted. Filthy and dangerous.”

“Yeah, maybe,” I agreed. “But it looks sexy, and I look sexy doing it.”

He shook his head and put forth a heavy sigh and stuck the ends of his stethoscope in his ears. He pressed the cold chrome cone to my chest and told me to breathe. Deep. Deeper. My lungs were clear, he said, grudgingly, when he’d finished the exam—despite the reckless behavior I’d chosen to embrace. He removed the earbuds and allowed the instrument to fall against his pressed white shirt. But while I finished dressing he advised me in the strongest language he could summon, to quit. Now. While I was ahead.

But I had no intention of quitting. Or slowing down in any way. As long as my headstone was locked up in the monument shop, I was going to do whatever I wanted. And what I wanted was to cut loose. Live like I’d never lived before.

By the end of the week, I was sporting a tattoo on my left arm.

By the end of the month I’d sung karaoke in the airport bar, eaten my first dish of Rocky Mountain oysters, and attended a purification ceremony in a sweat lodge with a small band of Ojibwe natives who lived in a commune on the western edge of town.

It wasn’t a bucket list. Bucket lists were for losers on their way out. It was a statement of resolution. A declaration of purpose. I wanted everyone to know that from here on in my only intention in this world was to live out loud, full volume, and never again go gently into that good night. I intended to come at life with the same reckless abandon Death had once come at me. Big, hairy, brawling. I didn’t know how long my luck would last or how long my tombstone would remain under lock and key. But I did know that, in the end, it didn’t matter. That what mattered was the here and now.

So I lived.

I lived like there was no tomorrow. I howled at the moon and danced like nobody was watching and embraced every moment as if it were going to be my last because, yes, even in my shiny new refurbished condition, I knew someday it would be.

By month’s end, my self-actualization process was fully underway. I worked at it, twenty-four seven, and was in the early stages of finding my way back from being the man I was to the man I am, when the oncology office phoned and insisted I come in for an unscheduled meeting. The call came as no surprise. It had been a while since Dr. Fleege and I had seen one another.

He walked into the examination room holding his laptop in his palm, acknowledging me without making eye contact.

“Ted.”

“Doc.”

He was scouring the screen, its light reflecting in the lenses of his expensive, tortoise-shell glasses, and in his free hand he clutched a ballpoint pen, which he clicked suspiciously while pacing the room.

I knew what was coming. I could see it. Hell, I could almost smell it, it was so palpable. The sour look on his face telegraphed the content of the entire conversation.

“How do you feel, Ted?”

I shrugged, affably. “How should I feel?”

He looked at me and blinked, his response timed for maximum gravitas. “You’ve got a terminal illness,” he said. “People with terminal illnesses generally feel pretty shitty.”

I smiled, turning up my palms. “And yet, here I am. Alive and happy.”

His eyes narrowed under the wrinkle of his long gray brow, and he tugged at his bottom lip with his thumb and forefinger. “Listen, Ted,” he said, taking up the sentence with slow deliberation. “I’ve got some difficult news.”